The Australian War Memorial, Canberra, was the brain-child of Captain C.E.W. Bean, lawyer, journalist, artist and war historian, who died in 1968.bean, was appointed Official War Correspondent to the first Australian Imperial Force in 1914. While at Gallipoli he recruited artists and writers among the soldiers to contribute to his Anzac Book, and this was probably the germ of his idea of a museum recording war in all its aspects as the nation’s War Memorial.

Conceived in 1917, the Australian War Memorial, after much argument as to its sitting, was inaugurated on Anzac Day 1929 and opened to the public in 1949. An impressive, domed, gray building, it is approached by a flight of broad steps and spreads across a low hill against a background of gray-green Australian bush land. From its elevated threshold one gazes down the broad vista of Anzac Parade across Lake Burley Griffin to the long, low, white line of parliament House, to Canberra’s enfolding hills and to the constantly changing backdrop of blue-purple mountain ranges.

The majority of visitors to the Australian War Memorial go to see the Hall of Memory with its golden mosaic dome, memorial windows (the work of Victorian artist, Napier Waller) and monumental sculptures representing the Services, to stand by the pool of Silence, flanked by the long Honor Rolls of the fallen, and also to see the tremendous collection of relics of war – the tanks, planes, submarines, guns, weapons of all kinds, the display of uniforms, accouterments, personal belongings and memorabilia of the valiant soldiers to whom the building is dedicated. Most people go there without a notion of the thousands of paintings, drawings and sculptures housed in the building, the work of many of Australia’s most distinguished artists; few realize the extent to which the paintings which crowd the walls enlarge their experience and even fewer appreciate how much the artists gave of themselves in producing these records.

Some were fighting men, some were wounded – Napier Waller lost his right arm – some were killed; the dedication and sacrifice of the artists were often as great and as demanding as that of the soldiery, and for many of them continued well after the war. The large canvases and dioramas that meticulously re-create the scenes of great conflicts, of the achievements and tragedy of war, represent months and years of intense concentration on the part of the war artists.

The aesthetic quality of the work in the Australian War Memorial is obviously uneven; temperamentally and in their artistic ability some artists ability some artists were much more suited than others to their best swift on-the-spot sketches, sometimes in oil but more often in water-color, with pencil or crayon; there are paintings whose value is purely as war record.

Without doubt the great strength of the collection artistically is in the work covering the First World War. Already in London and Europe at the outbreak of the war there was a large number of top-ranking Australian artists, artists of the caliber of Will Dyson, George Lambert, Arthur Street on, Tom Roberts, septum’s Power, Fred Least, George Coates and his wife, Dora Meson, Charles Bryant, A. Full-wood, John Long staff and also the painter of the famous Men in Gate at Midnight, 24th July, 1927. Others like Louis Cubin, George Benson, Frank Crosier, Daryl Lindsay, Balmier Young and John Moore joined the fighting forces. Captain C.E.W. Bean, artist and friend of artists, was well aware of the capability relied upon when it came to the appointment of Australia’s Official War Artists.

The first appointee in 1916 was Will Dyson, brilliant draftsman, already famous in London as satirist and cartoonist. He was twice wounded and his frontline drawings of life in the trenches and his war cartoons with their trench of satire and humor greatly enhanced his world-wide reputation. As his brother-in-law, Daryl Lindsay, his off-sider at the Front, said: ‘Dyson hated war with a resentful bitterness’ and in his work this comes through; his mastery of line speaks through body language of futility, tragedy, endurance, courage. He painted few oils but in these as well as drawings pose, gesture, express character and story in very human terms, even in paintings in lighter vein.

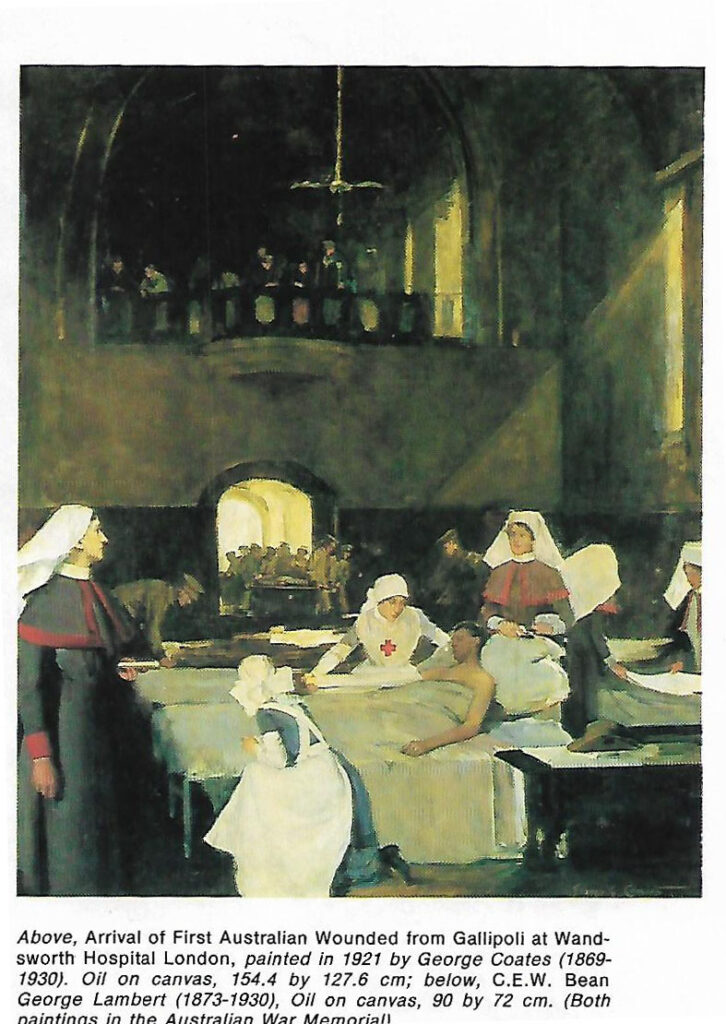

George Coates, poles apart from Dyson in his academic approach to painting, is of all Australian artists closest to him in this deep human sympathy and understanding of the tragedy and waste of war. Coates, who had an established reputation as portraitist in London was like Tom Roberts too old for active service and like Roberts spent the wartime years working as an orderly in the Third London General Military Hospital at Wandsworth. These years of menial work in the harrowing environment, constantly aware of the suffering of the wounded, the waste of the maimed, took heavy toll of these was commissioned by the Australian Government to paint portraits and records he produced such works as the classically composed Arrival of First Australian Wounded from Gallipoli at No. 3 London General Hospital, wands worth, 1915, at once a simply stated record and a dramatic indictment of a less glorious aspect of war.

Coates also painted some fine portraits, including that of the famous captain Albert Jackal, V.C. and the composite group Australian War Artists 1916-18, in which each of the men is shown as a fully characterized portrait. In the forefront of the picture is the flamboyant George Lambert – a pose similar to that in many of his self-portraits – and also prominent, virile and aggressive in stance in Arthur Street on. The war Memorial holds five hundred and forty-one drawings, sketches, water-colors and oils by George Lambert, an important segment of his total oeuvre and a high point of the museum’s collection.

George Lambert was at the peak of his career when in 1917 he was appointed Official War Artist with the rank of Hon. Lieutenant, later captain, attached to the Anzac Mounted Division, with pay of forty pounds a month and allowances. His first contract was for three months and in that time he undertook to provide ‘not less than twenty-five studies, sketches and drawings’. He had a further contract for ‘a large battle-scene in which the Australian Imperial Forces are to be represented for the sum of five hundred pounds’. The subject selected for this was The Charge of the Australian Light Horse at Beersheba.

George Lambert, the first New South Wales Travelling Scholarship winner in 1900, Julian Ashton’s favorite pupil, was a thoroughly trained academic painter and sculptor. An excellent draftsman, he specialized in portraiture, large-scale figure compositions and the painting of horses; he knew horses and was a fine horseman. He was, in fact, an ideal choice for war artist with the Light Horse in Palestine; although, as his letters show, he had a tremendous admiration and enjoyed a true camaraderie with the fighting men, his reactions were always dominated by the painter’s observing, penetrative eye. He found the commission exciting, challenging; its urgency sloughed much of his exhibitionism and drew from him some of his best work.

Soon after his arrival in the desert he wrote back to his wife: ‘I am ridiculously happy. Already I have done three pieces of work and everywhere I look there are glorious pictures, magnificent men and real top-hole Australian horses.’ The rugged terrain, hot, exotic color – his swift, tiny landscape sketches are little masterpieces – plus the difficult living and painting conditions and glut of subject matter stirred him to a perceptive spontaneity and simplicity of statement rare in his work. Lambert paid further visits to Palestine and Egypt and also, after the war, to Gallipoli to make studies for big pictures. Wherever he went he worked at white-heat; the large battle scenes he recreated back in the studio with crowds of men and horses, charging, retreating, living, fighting, dying, are the most artistically successful works in the Australian War Memorial. His The Landing at Anzac (190.5 x 350.5 cm) is an amazing tour de force and the tiny sketches of Palestine a sheer delight.

Arthur Stratton’s contribution to the collection is comparatively small – approximately ninety works, but it is in itself alone worthy of a visit to the War Memorial; a special exhibition of his sparkling water colors, drawings and oils, organized by the curator of pre-1939 art, Miss Anne Gray, after initial showing at the Memorial, is at present circulating through Australian State galleries.

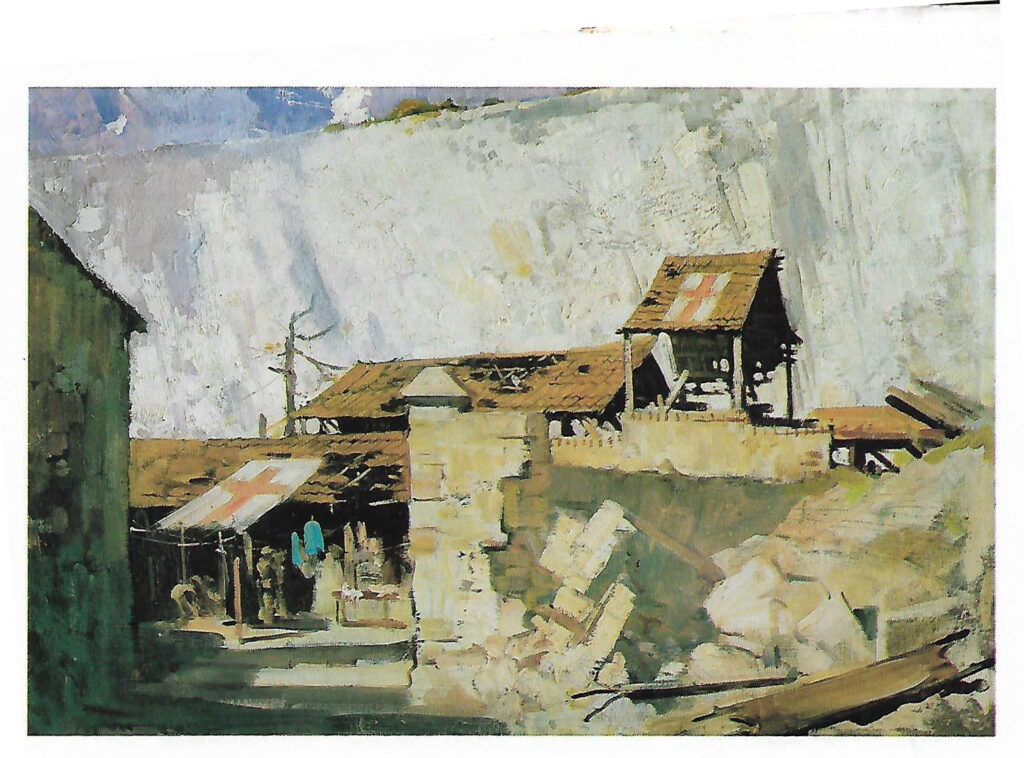

Arthur Street spent almost two years working at the Wandsworth Hospital ‘dressing wounds of the veterans of Mons and the Marne’ before in 1918 he was offered a commission to go to France as Official War Artist, a commission he seized upon with alacrity. He was attached to the 2nd Division of the A.I.F. on terms similar to those of Lambert, and he served in all for only five months, in that time producing some of his finest water-colours. As well as the water-colors and drawings done on the spot and some smaller oils, the memorial has three large compositions, painted from his sketches, without doubt three of major canvases in the collection.

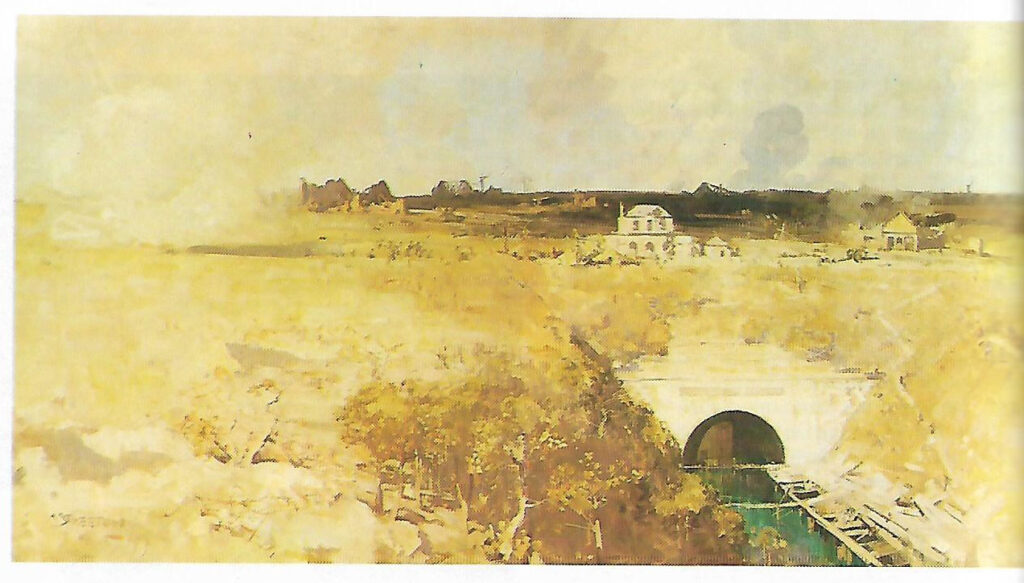

Streeton was not a figure painter; he was and he remained even in the war paintings a lyric landscape impressionist. With Tom Roberts, Charles Condor and Fred Cuban, back in Australia in the 1880s and 90s, he had forged a style and an approach to nature that became the foundation of the first national school; the Street on blue and gold vision of Australian landscape and light dominated Australian painting to a large extent for more than thirty years. It was this same vision and technical facility that gave vitality to Stratton’s wartime paintings of France. It is a desecrated landscape he paints, but his picture is still a hymn to the beauty of landscape, of light and shadow. Figures in his landscapes are rarely anything more than accents, and in the war paintings, except for the occasional water-color interior, the soldiery are never much more than dots in the distance; at most staff age, accessories, of the composition.

Probably the finest of the grand landscape is The Struggle for Bullecourt 29th sept 1918 – bare hills against a wide light sky, burnt-out buildings stark with dark accusing eyes, great illuminated puffs of white smoke, and below, the fooled tunnel, a subject similar to his famous Fire’s On, The Lapstone Tunnel, painted back in Australia in 1891. That Street on was deeply affected by the terrible destruction of war is evident in his letters, but even in war his painter’s deepest response was to landscape. He wrote back to Tom Roberts in London (31 July 1918): ‘It has been a grand day here and Isis at the tent door. I washed and changed early today and feel refreshed; below me the steep little gully, all green with upright trees, and the last afternoon light all golden like Australia catches the stems in patches and is diffused among the foliage in the most beautiful fashion.’ And he attacked his canvases with creative joy in the earth, dashing in his colorful, sensitive impressions with his characteristic broad, telling brush strokes and relish of paint.

Louis McCubin was a gentler, less ebullient impressionist, a young man of twenty-four when war broke out. He had studied and been a prize-winner at the Melbourne National Gallery School, where his father, Fred Cubin, friend and mentor of Street on and Roberts, the beloved ‘Prof.’ of the Heidelberg camps, was a teacher for more than thirty years. Like the sons of many distinguished fathers, Louis, as artist, worked always in his father’s shadow; that and the fact that in later life his time and energy were mostly absorbed by art administration – for fifteen years he served as a most able director of the National Gallery of South Australia – have tended to obscure his achievement as a painter. Louis Cubin joined the A.I.F.in 1915 and throughout the war did invaluable work, as did Bombardier George Benson and Lieutenant Frank Crosier in the topographical war records section; they were not appointed official war artists until September 1918.

For nine years after the war Louis Cubin was engaged, with the sculptors Web Gilbert and Wallace Anderson, who modeled the tiny figures in action, in creating the dioramas of battles which are such interesting and popular features of the War Memorial. He also completed large canvases, such as Going in through Sail-Le-Sec, and on a smaller scale a series of impressions illustrating the life of the soldiers in desert warfare – the isolation, the hardships and persistence, the shortage of water and dependence on the camel which were key factors in victory or defeat. Cubin’s service to the War Memorial did not end there; he was for many years a valued member of both the Australian War Memorial Committee and of the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board. In the Second World War he was called upon for the post of Assistant Director of camouflage.

Both George Benson and Frank Crosier had been students of the National Gallery School in Melbourne; Crosier, a talented but rather slap-dash painter, made a very extensive contribution to the records of the war in France. Benson, who specialized in water-color, contributed a few relatively small oils, very distinctive with their light, decorative character and obviously influenced by art nouveau.

Appointed Official War Artists in France in 1917 were H. Septimus power and Fred Least; Charles Bryant also went to France but later with Arthur Burgess – both were already acknowledged marine painters – was commissioned to cover the war at sea. Their large canvases record naval engagements and signal events, such as Bryant’s H.M.A.S. Sydney’s Encounter with a German Zeppelin in the North Sea, 4 May 1917, and Arthur Burgess’ Australia Leading port Line at German Surrender, 21 November 1918.

Septum’s power and Fred Least, both born in 1878, were in the thick of the fighting in France. A New Zealander, power came to Australia when he was twenty and pursued his studies in Paris; he specialized in the painting of animals, especially horses, of which he made a careful anatomical study. His many large canvases of men in action are painted with extraordinary vigor, the swift, broad brush strokes laid on with knowledge and assurance. There is violence and urgency in his Third Ypres31 July 1917, taking the Guns Through. It is a bold composition and his work lacked the subtlety of color and draftsmanship of Lambert or Street on, it is down to earth and carries involvement and conviction. Septum’s power also painted some stirring scenes of the action in Palestine, featuring the camel corps and also in a large canvas the participation of the embryo Air Force of the time, with its perilously fragile places.

Fred Least, a brilliant student of Julian Aston, early had considerable success as illustrator both in Sydney where he worked for The Bulletin and in London after 1908 on The Graphic. He handled with an easy flair such complicated subjects as crowds and race scenes, as well as portraits and individual figures. His war work is remarkable for the direct crispness of his water-colors, his capable handling of subject matter of all kinds. A realist, he relied on his keen observation, draftsmanship and strong sense of pictorial composition. His large paintings, such as Mont St Quentin are sound and convincing portrayals; after the war his ability to handle large compositions successfully led to important mural commissions in England and America.

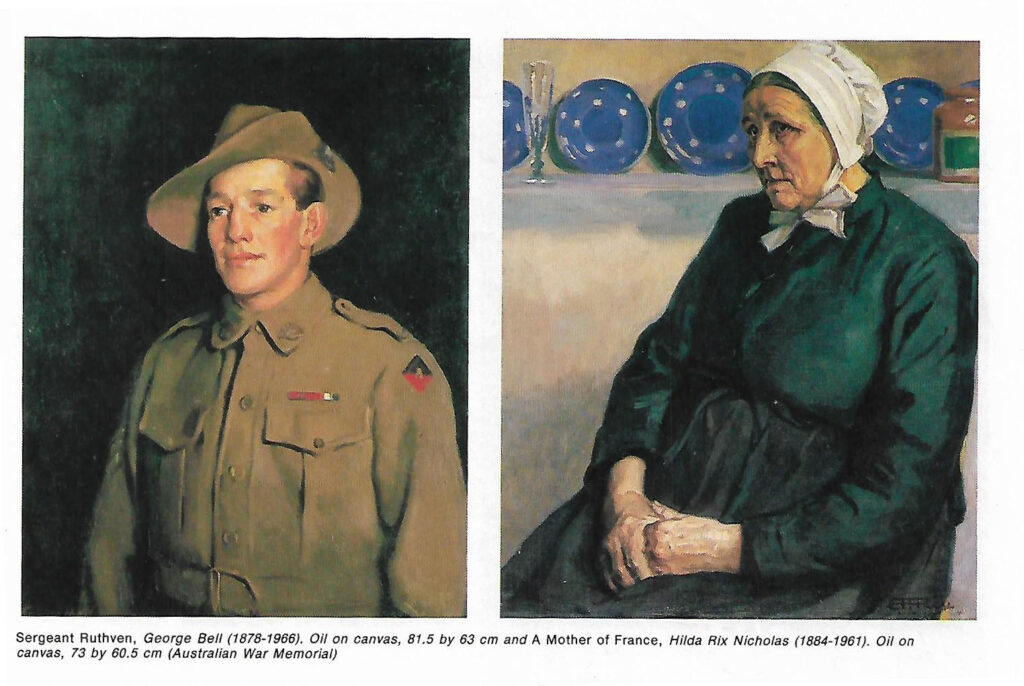

George Bell, who figures prominently in the story movement in Melbourne – with Arnold Shore he founded the Bell-Shore School of Modern Art in 1932 – was also in France. Bell had followed up study under George Coates in Melbourne with some years in Paris and had an established reputation in London and Europe, particularly for his portraiture, when war broke out. He was elected a member of the Modern Society of Portrait Painters in London, which challenged the portrait painters in London, challenging the prevalent recipe for dull, formal portraiture.

Bell worked in munitions before receiving his appointment as Official War Artist. Unlike street on, Bell, with less bravura than power, portrayed the dreariness of the desolate battlefields; he depicted weary, muddied men patiently laying duckboards needed to move about at all in the heavy mire. No doubt he regarded his oil landscapes as his most important records of the war, but his water-colors – he handled both media with skill – are delightful souvenirs of his pleasure in the surviving charm of old French villages.

Charles Wheeler joined the Royal Fusiliers, was severely wounded and awarded the D.C.M.; he is said not to have touched a brush during the war. A product of the National Gallery School in Melbourne, where he later taught for a number of years, he had also studied in London and Paris and London and Paris and was recognized as an accomplished painter of the figure after the manner of Velasquez. He received a number of commissions for war painting; large canvases, large canvases, conscientiously painted, thin and rather ghostly compared to the work of the Official War Artists, and they depict life as he must have lived it on the battlefield, day and night: barbed wire, prone figures, a sad recall. Wheeler also painted a number of sensitive portrait commissions.

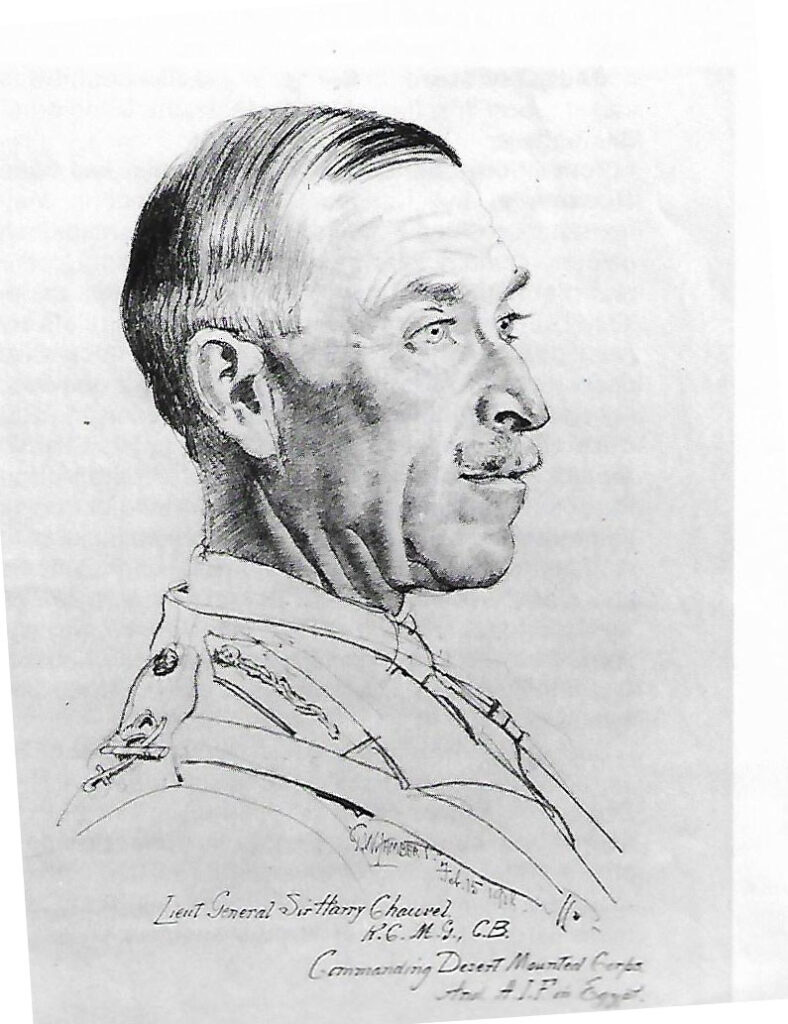

Portraiture is a large and absorbing area of the Memorial Collection, and here again quality is uneven. Academic commissioned portraits tend to be dull and the repetitive khaki uniform gave the artists little flexibility of color or pose. There are, however, a number of paintings by leading Australian portraitists of the period, such as General Monish by Sir John Long staff, Lieutenant-General Sir Harry Chauvin by W.B. McInnis, James Quinn, an Official War Artist, Bernard Hall and Florence Roadway all ably fulfilled portrait commissions.

Particularly notable among the portraits are Hilda Rid Nicholas’ painting A Mother of France, which with its patient dignity conveys the courage that sustained the home front, and George Bell’s giant W. Ruthven V.C., a sensitive portrayal of young, idealistic heroism; also the works of George Coates, which include a large composition of General Bridges and His staff Watching the Men oeuvres of the 1st Australian Division in the Desert in Egypt, 5 March 1915. The formally arranged figures, grouped against the background of pyramids and desert, each man meticulously portrayed, gave the artist many problems and took him, with the help of his artist wife, Dora Meson, four years to complete.

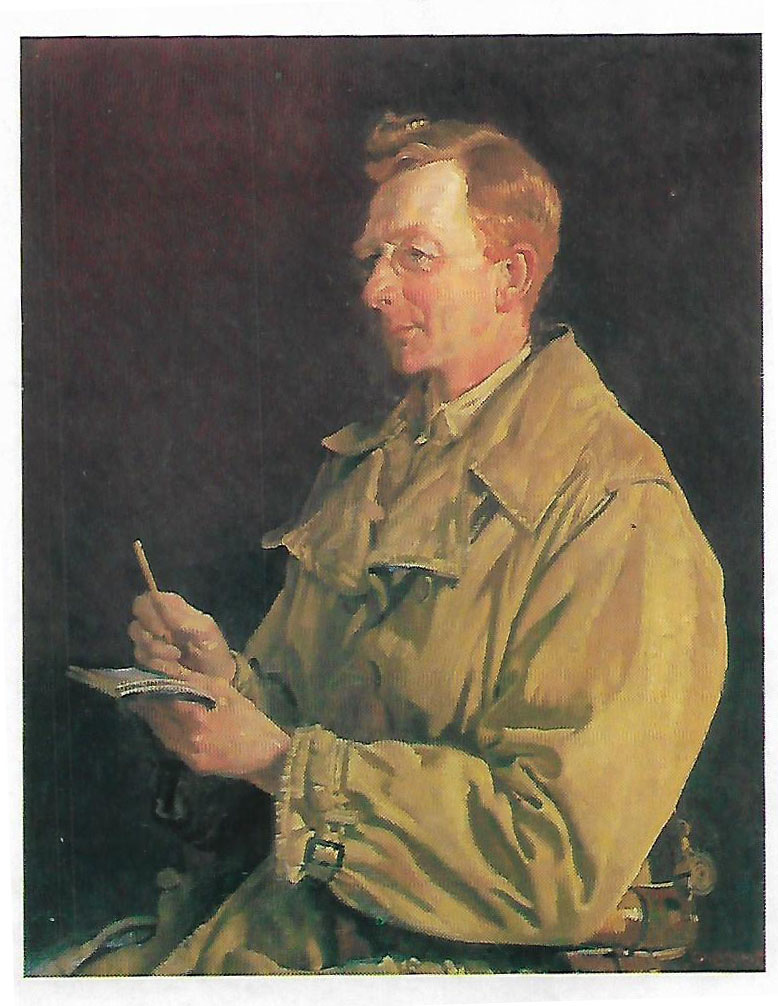

But in portraiture, as in the large battle scenes, it is George Lambert who makes the deepest impression. There is an intense vitality in his remarkable series of pencil drawings of officers and men, many swiftly noted whilst they were about their duties, and he also produced a number of official portraits, not least among them a quietly penetrating tribute to the imaginative and scholarly Dr. C.E.W. Bean, instigator of the War Memorial.

Leave a Reply