Illustrated Manuscripts of India and Southeast Asia

The illustrations which adorn the traditional manuscripts of South and Southeast Asia provide a rich repository of the imagery of cultures of ‘Indianised’ Asia. Diminutive in size, and often devoted to unfamiliar and esoteric iconographic content, they are often overlooked in surveys of the art of the region. The production of traditional illustrated manuscripts was the preservation and dissemination of the revered religious texts and the great literary epics but by virtue of the illustrations they contained, these manuscripts also became the custodians of an otherwise largely lost pictorial tradition.

The traditional manuscript of India, and of those countries which were touched by her cultural influence, consisted of a group of separate folios trimmed to a narrow, horizontal shape. A binding cord was threaded through each folio and around a pair of wooden protective covers which held the folios firmly together. The folios were traditionally prepared from the leaves of the palm- tree which were treated and then trimmed to the required proportions. The text and any decorative detailing of illustrations were then either applied by brush or incised into the surface with the aid of a metal style (or stylus). With the introduction of paper the use of palm-leaf was largely abandoned, but the proportions of the traditional palm-leaf page, and the pictorial conventions which had accompanied it continued to influence the appearance of South and Southeast Asian manuscripts for many centuries.

The precise antiquity of the palm-leaf (pithy) is unknown though there is little reason to doubt that it extends back in time almost as far as the art of writing itself in India. Engraved copper plates retrieved from the ancient city Axial, dating from the first century AD, are of a narrow landscape format, presumably already emulating the palm-leaf folio. Buddhist tradition claims that the scriptures were first Buddhist Council of 483 BC, but a later date is generally accepted on textual evidence. The Jain scriptures are believed to have been committed to writing as late as the fifth century AD, prompted by a severe famine which threatened to break the chain of oral transmission. Such texts would almost certainly have been executed on palm-leaf, or on another ancient writing material, birch- bark (bhurja patra). Birch-bark as a medium for writing in India is mentioned by first century AD Greek historians. The earliest fragments extant, dating from the second and third centuries AD, indicate that, like the earliest copper-plates, they follow the palm-leaf format.

The earliest palm -leaf manuscript known is a fragment of the text of a second century Indian drama, written by Asvaghosha, which was discovered in central Asia. A number of early sculptural depictions of palm-leaf format manuscripts, as seen for example at Eula and Borobudur, attest to the importance attached to copies of sacred texts. The Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) text was so revered that not only was the manuscript itself the object of worship but the essence of the text was personified in a goddess of the same name, through whom devotion could be directed. Deities such as Manjushree, Sudhanakumara, and Prajnaparamita are represented holding a sacred manuscript as one of their principal attributes.

The sources for the study of the origins of these manuscript painting styles are diverse. The earliest pictorial evidence, mural paintings which represented the ‘great tradition ‘of Indian art, survive, with the exception of Ajanta, only in a fragmentary state. The gaps in the chronology are as great as the periods represented. Dating is aided by the study of parallel developments in sculpture; the aesthetic treatises attest the close stylistic interdependence of the plastic and visual arts in ancient India, while theological developments generated parallel shifts of interest in subject matter.

Early literary sources alluding to the arts are frequent in India, many dating from early in the first millennium and belonging to the rich Sanskrit tradition of the day. References abound to the presence of paintings, most of which are presumed to be murals, in both religious and secular settings. By at least the sixth century AD, elaborately formulated treatises on aesthetics had been written, setting out the desirable qualities of painting in formalist, if rather generalized, language. Connoisseurship was cited by Tatyana in his famous fourth century guide to the pleasures of life, the Kama sutra, as one of the dilettantes of his day.

Despite the considerable visual, archaeological and textual evidence of the early existence of the palm-leaf manuscript, no illustrated texts have survived which are earlier than the tenth century. The earliest examples are almost exclusively from the Eastern Indian region of Bihar and Bengal. Paper made its appearance around the twelfth century but did not displace palm-leaf until the fourteenth century. The introduction of paper freed the manuscript painter from the highly restrictive format dictated by the palm-leaf, which typically allowed illustrations of only five by eight centimeters inserted in the text. The wooden covers accommodated more elaborate compositions in a continuous narrative format. Whilst the paper imposed no such restrictions, convention ensured that the format persisted for centuries. A typical Jain paper manuscript folio is ten by twenty centimeters. The scribe continued to dominate, setting aside a rectangular space which the painter would complete.

It was the writings inspired by the religions of India which provided the greatest stimulus to the pictorial arts. Illustrations of deities and saints are an ever-present subject, as are scenes from the lives of Prince Siddhartha and Mohair, the founders of the Buddhist and Jain religions respectively. Scenes from the former lives of the Buddha as told in the Pataki stories are a recurring theme, as are similar legends recounting episodes from the lives of the twenty-four Jain saints (tirthankaras). The two great Hindu epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana remained a constant source of inspiration for the pictorial arts of India much of Southeast Asia.

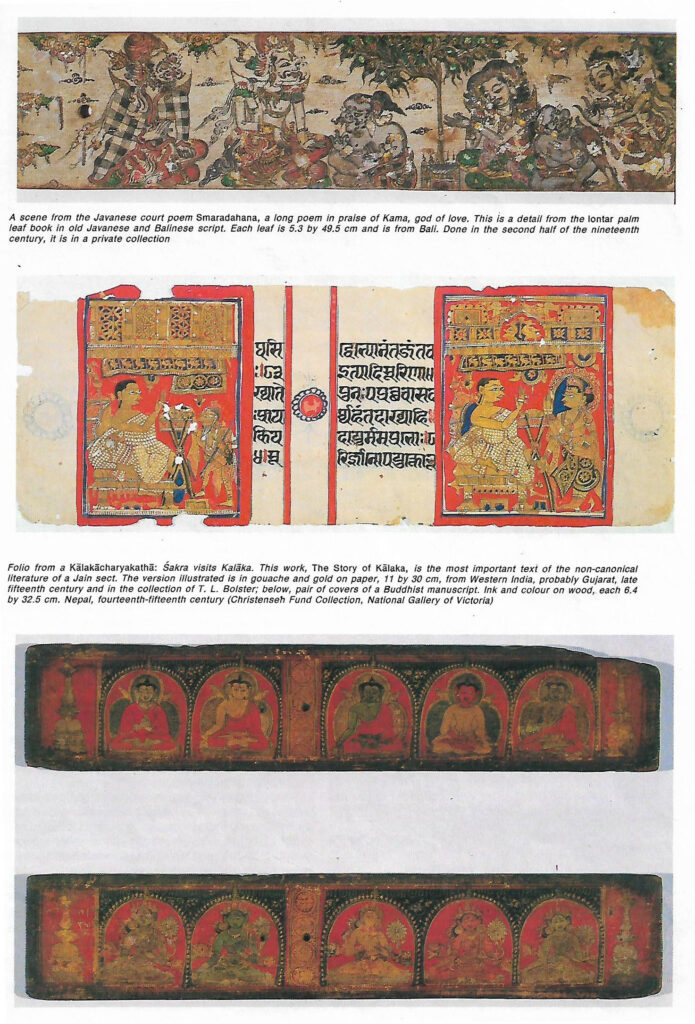

Illustrated manuscripts produced in the service of Buddhism are amongst some of the earliest extant examples. Whilst the survival of illustrated palm-leaf folios from the end of the first millennium is very rare, the more robust painted wooden covers survive in greater numbers. The pair of covers for Buddhist manuscripts are decorated with the five dhyani buddhas (Buddha in meditation) and the five of the twenty-one forms of Tara (Saviouress). Each figure is set against a back plate edged in flames, reminiscent of ninth-tenth century bronze images from the Buddhist monastic center of Malinda and elsewhere in Eastern India. The paintings exhibit a continuation of the Eastern Indian School, and represent the last phase of that style, as preserved in Nepal.

A unique feature of the early Buddhist illustrated manuscripts was the relationship of illustrations to text. Rarely do they actually illustrate the subject of the text. Typically they provide an iconic representation of a deity, or a scene from a Pataki story not described in the text. Their function therefore would appear to be limited to assisting the devotee in concentrating his worship, giving focus to his meditation. Through illustrations of this kind the manuscript itself became an object of worship. The wooden covers of early manuscripts bear witness to this practice, the painted surfaces of the exterior being often totally obscured over centuries of ritual worship by the daubing with sandalwood paste, oil and milk.

‘Sakra Visits Kalka’, a folio from a Kalakachar-yakata manuscript, displays the typical conventions of the Jain style of Western India painting. The stress is on linear expression of a peculiarly angular form and a limited but vibrant color scheme. The distinctive characteristic of the protruding eye seen beyond the facial profile is peculiar to this style. The left hand illustration depicts Sakra (Indra), the King of the Gods, appearing before Kalka in the guise of an aged Brahman. Kalka sees through the disguise and Sakra then assumes his divine form, depicted in the right-hand panel. Each figure is painted in gold, the white robes of Kalka designated by white dots which vibrate against the brilliant red background. By the sixteenth century in western Indian painting the illustrative component had, on occasions, taken over the entire surface of the page.

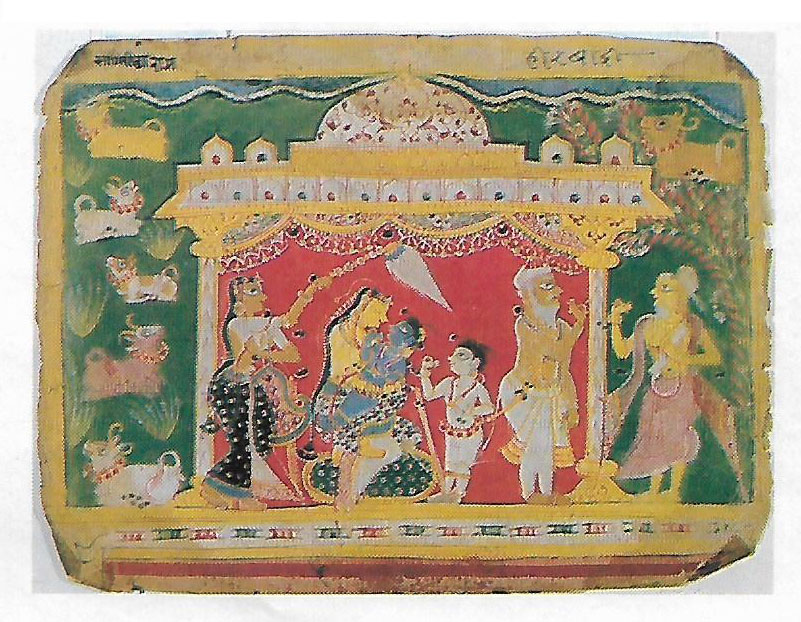

One of the most popular and recurrent subjects for paintings based on Hindu sources were events in the life of Krishna as described in the Bhagavata Purana. ‘Yasoda Nursing the child Krishna’ depicts the blue-skinned infant being nursed by his foster-mother Yeshiva whilst his brother Balaam stands close by. Each child is naked but for ankle and wrist bracelets, and other adornments, the typical attire of young infants in India today. To the right appears the turbaned and bearded figure of Nanda, Krishna’s foster-father, who is seen engaged in conversation with a sage-like figure who holds the leaf of a manuscript (?)In his left hand. Both men are finely dressed and of noble disposition. Nanda displays a dagger of princely quality. Shod and Krishna are being fanned by a young woman holding a chary. The family group is set in an open pavilion with a handsomely decorated dome, turrets, and projecting eaves. It has arabesque designs on the dome and capitals, lotus petal motif on the columns, and is decorated with tasseled verandah hangings. Sweetly smiling cows fill the landscape, evoking the theme of vastness (‘calf-love’), and the spirit of devotion which the worshiper should feel towards Krishna. The popularity of this theme in seventeenth century North Indian painting was a reflection of the wide-spread Bhatia movement which stressed loving adoration of the deity, ranging from the theme of maternal love seen in the subject of this painting to erotic love, revealed through the theme of Krishna’s dalliances with the cowherd women (gopis). This painting belongs to a group of illustrated manuscripts of uncertain province and date, known as the ‘kuladhar’ group after the style of turban depicted. They conform in style to the famous Chaurapan – Chaska paintings and may predate that series judging from the freshness and vigor of both conception and execution. Mewari in Rajasthan and the Delhi-Agra region of North India have both been suggested as the source of these paintings. Their relationship with the Western Indian painting style, particularly in the female figure-type, the angular profile and the ‘fish-eve’ convention, and the wavy cloud motif, support a Rajasthan provenance. The Islamic inspired architecture suggests links with the pre-Munhall Moslem Sultanates of North India but may also be explained through Western Indian sources. Perhaps the strongest argument in favor of a Rajasthan attribution is the essentially Hindu flavor of these paintings. Warmth and humanity pervade the paintings which take as their unifying theme the expression of passionate love, be it in a secular Sanskrit love poem, such as the Chaurapanchasika (Tales of a Love-Thief), or in the sacred literature devoted to the worship of Vishnu in his much-loved manifestation as Krishna.

The impact of the Hindu-Buddhist world on the early cultures of mainland and insular Southeast Asia touched all aspects of cultural expression. The medium of transmission of South Asian painting styles to Southeast Asia was, most probably, intimately associated with the transmission of the religious and literary traditions. The court cultures of the early Southeast Asian kingdoms were heavily ‘Indianised’. The influence of Indian culture was to be seen most directly in the use of Indic scripts, the extensive word borrowings from Sanskrit, the adoption of Indian concepts of kingship and associated religious practices. The traditional arts of Southeast Asia were largely untouched by Islamic culture until the fifteenth century when the process of Islamisation began in the Malay world. The art of manuscript illustration in Southeast Asia after that time is largely confined to the Hiragana Buddhist world of Burma and Thailand and the archaic Hinduism preserved on the island of Bali.

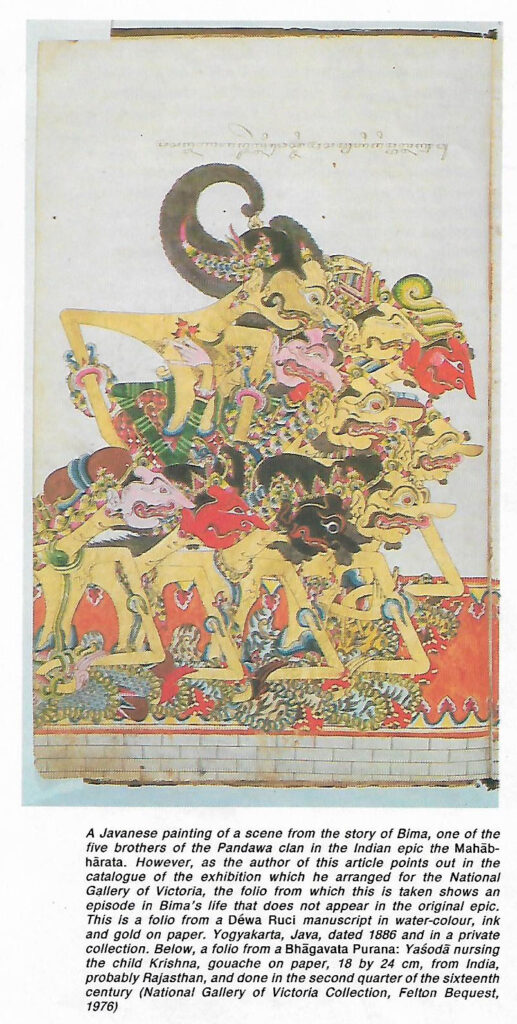

As in India itself, the favored subjects for depiction in temple decoration were episodes from the previous lives of the Buddha, the Pataki stories, and scenes from the great Hindu epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Little evidence of painting survives in the region before the twelfth century with the exception of Sri Lanka. However, there is no reason to assume that painting was not extensively practiced, along with the arts of temple building, stone carving and bronze casting, all of which reached standards of technical and aesthetic excellence which rivaled their Indian models. The island of Bali perpetuated elements of an earlier style of painting which derived in part from East Javanese sources and ultimately, from Indian itself. ‘An Illustrated Manuscript of the Smaradahana illustrated a Javanese court poem (kaka win) in praise of Kama, the god of love. Whilst the principal themes of the poem, Siva’s penance and Kama’s punishment, are well known in Indian literature, they do not belong to either of the great epics and their precise source is difficult to determine. The lively and expressive quality of these illustrations identifies this manuscript as belonging to the mainstream of traditional Balinese Hindu art. The mannerisms which characterize the style are clearly evident: the juxtapositioning of the noble and plebeian figures, the characterization of types. Elements of naturalistic observation contrast with the fantastic imagery which the artist has conjured up in response to the text. Thus an essentially Balinese character is given to the visualization of the Indian text.

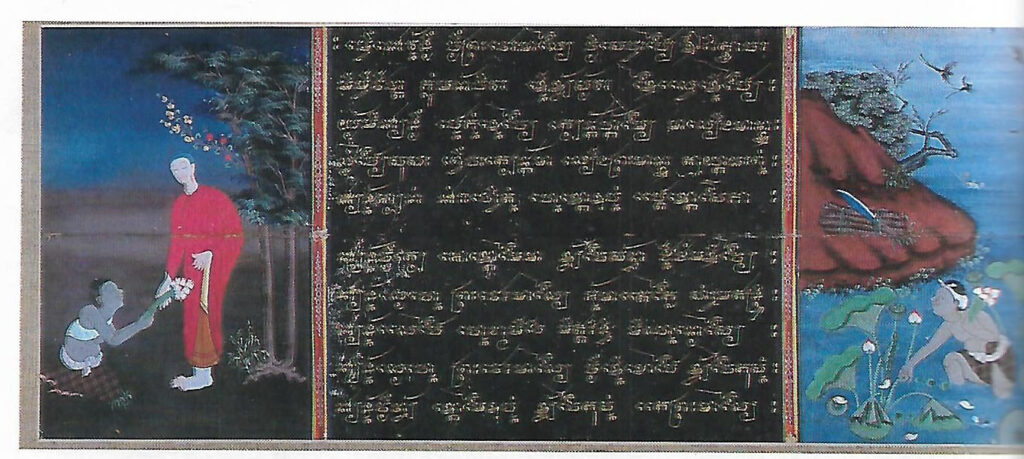

A growing awareness of European artistic conventions is evident in the late manuscript painting styles of mainland Southeast Asia. A traditional Thai Buddhist text, such as the Par Malay, a moralizing poem recounting the experiences of a Sinhalese monk in his journey to Heaven, was by the mid-nineteenth century illustrated in a naturalistic style. ‘An illustrated Par Malay’ depicts a humble woodcutter collecting lotus-buds from a lake to present to the monk Malay, exemplifying the meritorious practice of making gifts to monks. The naturalistic treatment of the landscape setting and the delightful attention to detail suggest an awareness of nineteenth-century European conventions. Under Rama IV, King Mongkut, of Thailand (1851-68), such an interest was actively encouraged to the detriment of the traditional Thai style. The text is written in the Cambodian script (Khom), Which continued to be used for the sacred Pail literature after the Thai script was developed and was only known to monks specially trained in its use.

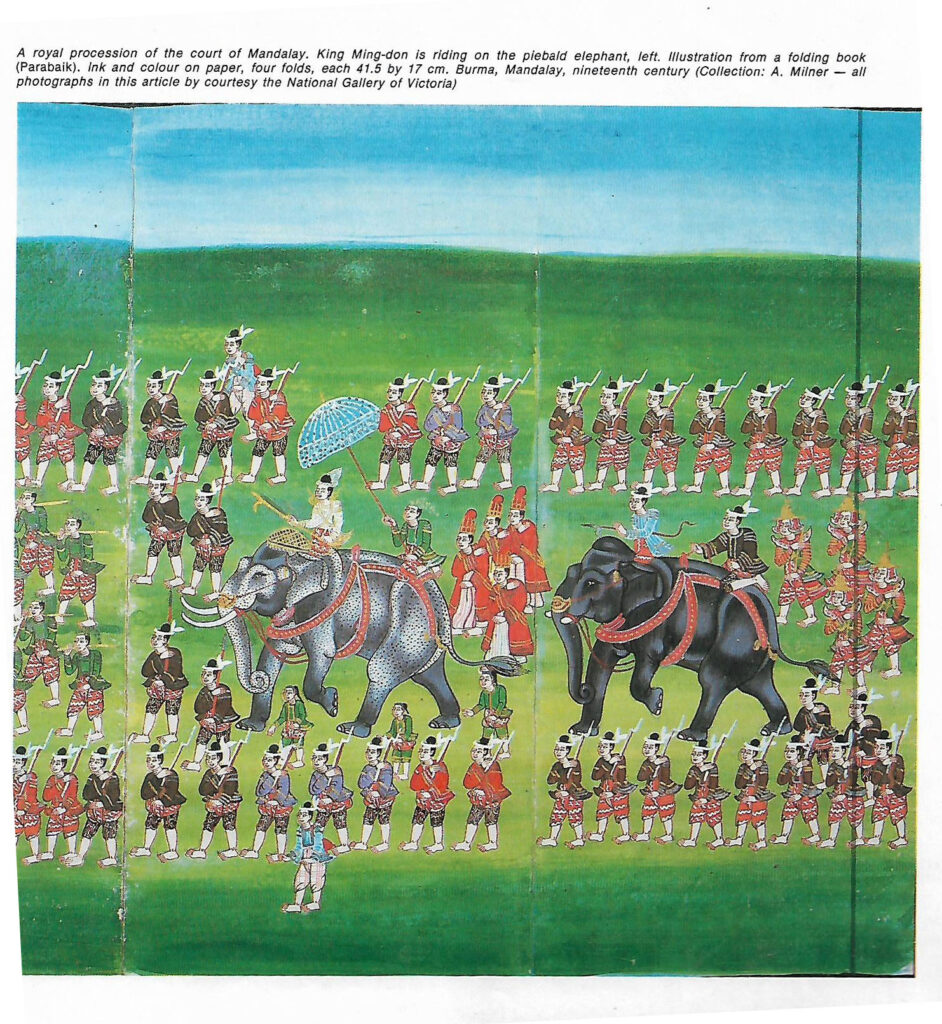

A similar response to the European influence is seen in manuscript painting at the royal Burmese court. ‘Royal procession’ is a popular subject for depiction in parabolic manuscripts at the court of Mandalay in the latter half the nineteenth century, along with scenes of elephant training, boat racing, puppet displays and other courtly entertainments. One of the finest extant paintings of this type, The pageant of King Min- don (British Library) records an historic event which occurred in 1865. The painting is undoubtedly based on the artist’s direct observation of the pageant and probably does not greatly post-date the event itself. This work conforms to the style of the 1865 painting in its composition organization, figure conventions and costume details. It was most probably executed between 1865 and 1885; the year British forces captured the royal palace at Mandalay. The painting bears a caption, added later, which reads: ‘Picture of a journey by land of the Burmese king and royal officials’. It depicts the king, identified by a white umbrella held overhead, riding a gray-spotted elephant. A second elephant follows and both are encircled by ranks of armed soldiers in a variety of uniforms. Four of the king’s ministers, in red robes and tall hats, walk behind the royal elephant. A curious feature is the depiction of tattoos, painted as black swirls on the upper legs of the soldiers grouped around the king’s elephant. (The practice is also known in northern Thailand and seen in paintings of the Thai Lana School.) The drawing and modeling of the elephants is very accomplished and instills considerable vitality into the scene. The figures appear as lively but repetitive images painted in outline and wash with no attempt at tonal modeling.

Although the religious and literary traditions which produced these manuscripts are still very much alive, they no longer require transmission through the traditional medium of the handwritten manuscript. With the passing of that need, the motivation to produce the splendid paintings which accompanied them has also passed. The variety of styles, and their transformation through time, provides a valuable insight into the stylistic development of the pictorial art of India and dynamics of interaction with those countries touched by its culture.

Leave a Reply