The large metal plate is placed carefully face up on the press, and maneuvered into place. Now an assistant, with gloved hands, takes a sheet of dampened paper and gently lowers it on the face of the metal. There is no allowance for final adjustments. The decision has been made on where the print will appear on the paper. Thick felted wool blankets are placed to protect the plate from the savage pressure of the press. Now the large handle wound forward. The bed moves plate and paper between the heavy rollers and out on to the other side. The blankets are lifted, the paper removed, and a freshly printed etching is revealed.

Lionel Lindsay once described etching as ‘the black art’. I think he was right. There is something medieval magic about the process whereby intricate lines and delicate half tones are eaten into a plate with acid at the command of the artist. So technically precise is the knowledge required, and so hard to control the inking of the plates, to make each print consistent with the rest of the edition, that many artists have traditionally used print workshops where master etchers, who may or may not themselves be artists, help them interpret their work in this mystical medium.

The most surprising of these workshops in Australia is probably the Griffith workshop in Sydney. It is surprising not so much for the sheer technical excellence of the prints produced, or for its well equipped, generously planed spaces, but for its setting. In Sydney, centers of art activity are usually associated with the inner city, Eastern Suburbs and even the North Shore, but Bardwell Park is the last place one would expect to find a fully fledged etching workshop. Bardwell Park is a suburb on the East Hills line, a place of double fronted red brick cottages, white collar workers and small businessmen.

Pamela and Ross Griffith’s house is different. A natural brink building, hidden in the corner of a quiet street, does not obtrude its good taste. Inside, the bush land garden which shields the house from the golf course creates the feeling of another world. Pamela Griffith is also surprising. She glides smoothly into a variety of roles. She is an etcher of others’ works and an artist in her own right, a teacher, a mother and the wife of academic Dr Ross Griffith, a senior lecturer in textile Technology at the University of New South Wales.

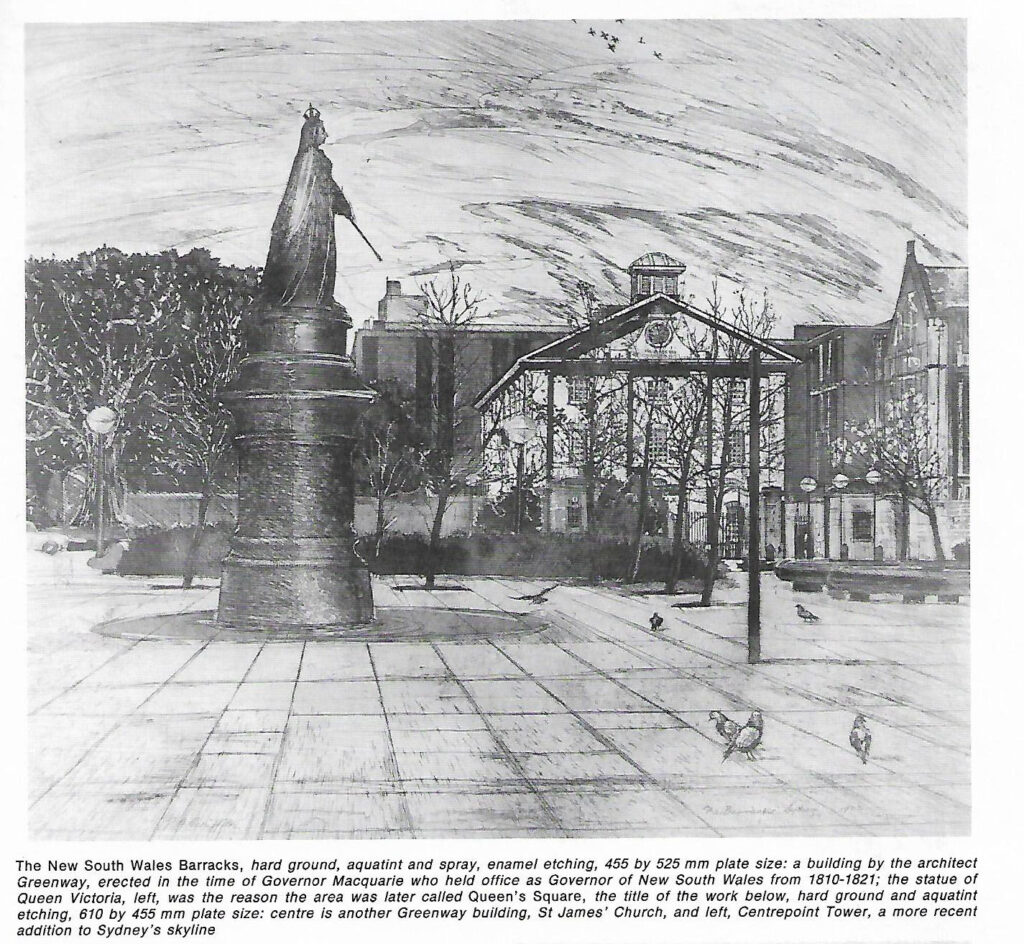

Pamela Griffith was born Pamela Dittoes, the daughter of a former Secretary of the New South Wales Department of Main Roads. From her administrator father she gets a sense of order and achievement through thorough preparation. From her mother’ side she inherited a tradition of women being successes in their own right. A woman ancestor had run a factory in the 1830s, a time not noted for like her brother, artist George Dittoes, Pamela has controlled exuberance with a dash of wit which permeates her art. Is it accidental that Queen Victoria is apparently saying ‘Off with Their Heads!’ to the birds in Queens Square? Or is it part of an elaborate joke by the artist?

The artistic development of Pamela Griffith and the Griffith Workshop is a reflection of the fluctuating status of etching in this country. When she was student in the late 1950s etching was not taught in the early years of this century- artists like Lionel and Norman Lindsay, Sydney Long, Jessie Trail and Sydney Urea Smith – were dead or had ceased working and their art was out of fashion. The market for cheap multiple forms of art had been destroyed by the Depression and the post – war generation of artists rejected techniques associated with conservative traditions. They had been so concerned with liberating art from the tyranny of skill that they rejected a craft that traced its origins back to the Renaissance works of Albrecht Durer. But etching, although a great and time-con-summing skill, is also concerned with managing to manipulate seeming accidents. An etcher can be involved with the savage energy of Goya as well as the delicate harmonies of Whistler.

At about the same time as Australian artists were turning their backs on bitten metal, European artists were looking at the old medium with new eyes. They saw that the technical innovations of the twentieth century could be made to work in etchings. In particular they discovered that different qualities of different colored inks could be used to create multi- colored etchings. So many savant- grade artists turned to the revived medium.

This did not help those art students in Australia who were interested in etching. Even though Lionel Lindsay had caused the Art Gallery of New South Wales to acquire some superb old master prints in the 1930s and 1940s, by the 1950s they were rarely if ever on view. In Melbourne where the National Gallery of Victoria had an extensive print collection the position was better, but limited exhibition space meant there was no easy access to the public. Other states also neglected graphic art by declining to display most of the prints which were available.

For Pamela Griffith the introduction to the art of etching came suddenly. In 1960 the artist David Strachan (see Hemisphere October 1976) returned to Sydney after an absence of twelve years. Although primarily a painter, Strachan had made some etchings in the early 1950s when living in Paris. He did not continue as a printmaker but when he returned to Australia he brought his etching plates and some of his prints with him. A fellow student told Griffith about the new teacher who had etching plates, and, curiosity aroused, she went and saw them. She was entranced by the beauty of the bitten copper and from that time on she knew that she wanted to be an etcher.

But etching classes were not available. So she decided to teach herself. Artist Strom Gould who had in the past done etching gave her advice and encouragement and when in 1961 the Sydney print- makers Group was started she was able to identify those practicing artists involved in etching. To learn etching Pamela Griffith went to the classic text, E. S. Landsman’s The Art of Etching, written in the 1920s and bituminous grounds from the recipes in Landsman’s book as none was readily available. Old presses, left in strong form when etching had been taught many years before, were brought into use by Pamela and other students interested in the revival. When the National Art School started evening classes in etching in 1965 she enrolled, largely to get access to the presses. In 1966 she managed to make her own press, adapted from an old wooden clothes mangle. But art school conditions and home-made presses do not really make exhibition quality prints. Not for perfectionists anyway.

These early etchings were made in traditional etching techniques. A ground of a mixture of bitumen and wax (now commercially available) is rolled over the heated plate to shield it from the acid. The etcher then draws on this with a metal-tipped tool. No pressure is needed as even the lightest stroke breaks through to the metal. The plate is then dipped into a bath of acid. Those lines which the etcher wants to print lightly are then stopped out with varnish and the plate re- bitten to get stronger lines. It is possible to get a ground so sensitive that it will show the texture of materials, or transfer drawings traced on paper placed on it. This apron- privately enough is known as soft ground. Subtle variations of tone can be added using aquatint, so called because it makes a printed plate look like a watercolor. Fine grains of resin are baked onto the plate. When the plate is dipped into acid it does not bite on the resinous spots, thus making a grainy tonality.

After leaving art school Pamela Griffith taught in high schools for a number of years until she felt she should broaden her experience. She wrote a book, The Road makers, a history of N.S.W. roads, married and had children. For the past ten years she has taught in tertiary institutions.

To understand Griffith’s development as an artist and her relative obscurity until recent years it must be appreciated that the early 1960s were not a favorable time for women artists in Australia. The sexually oppressive attitudes of the 1950s continued well into the next decade. Griffith remembers with some bitterness the well known Australian artist and art educator who told her that ‘we’ did not want too many women artists. So her development of a perfectionist skill was largely in private. This private development of her art, along with her involvement in teaching, can be seen as a retreat from an impossible situation.

In 1927-73 Griffith, her husband and their baby daughter traveled in Europe. Here she gained valuable workshop experience in England, Germany and Israel. The great English etcher Frank Short used to say that to print an etching properly the printmaker had to have ‘the palm of a duchess’. To ink a plate for printing it is warmed and covered with oil- based ink. Most of this ink is removed by wiping it first with Tarleton and then with the printer’s hand. This last stage is crucial and it takes many years to judge the exact amount of ink which should remain on the plate and to do it correctly. As well as working with master etchers Griffith also saw the exciting possibilities made available by new technology. On her return to Australia Griffith set up her own etching workshop, realizing that a woman with children cannot use other people’s presses to make quality prints.

With the support of her husband she borrowed money for a studio extension to their house. When presses were unavailable she designed her own. Instead of a converted mangle she now has three presses (including one for lithography), two heaters for warming plates, an aquatint box, a darkroom including a vacuum box, and a carbon arc lamp. Until suitable paper became available in Australia she imported her own and even now she imports much of her own equipment.

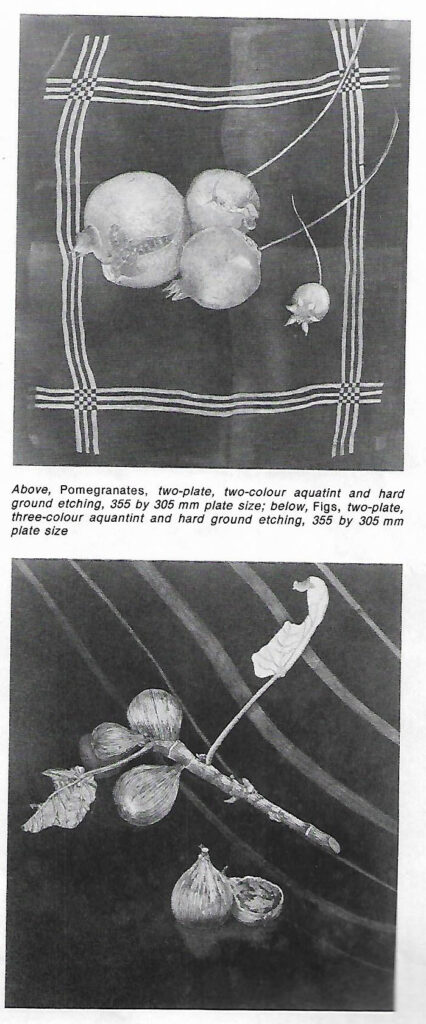

Gradually she has built up a reputation as a perfectionist printmaker, making etchings for others as well as printing her own work. Such is her emphasis on perfect technique that artist Blake Twig den, whose etchings she prints, has dubbed her ‘Do it correctly Griffith’. Her own work has evolved through an involvement with natural forms. Careful drawings from life of flora and fauna are wittily related to other more artificial shapes. Some of her Australian subjects are in the collection of the New South Wales Parliament house and others are in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney.

Her first etching on an architectural subject was made four years ago. The Old Brewery, Wagg captures the feeling of a country town on a lazy afternoon. The street is wide but empty. The only inhabitants are the ducks in the foreground. The old building, now an art gallery, faded by the sun. This etching was made as a demonstration print when the artist was exhibiting in Wagg, but it stands on its own as an evocation of rural Australia.

Last year Pamela Griffith was approached by the Museum of Applied Arts and Science to make a series of etchings commemorating the opening of the new Old Mint and Barracks Museum. The artist’s family has had a long association with architecture; an ancestor designed the classic Georgian buildings in Dublin which are some of the finest features of the city.

As a student Griffith had written an essay on Greenway, the architect of the barracks. She has always admired his energy, restraint, and especially his ruthless search for quality craftsmanship. ‘Do it correctly Griffith’ understands that kind of passion for perfection.

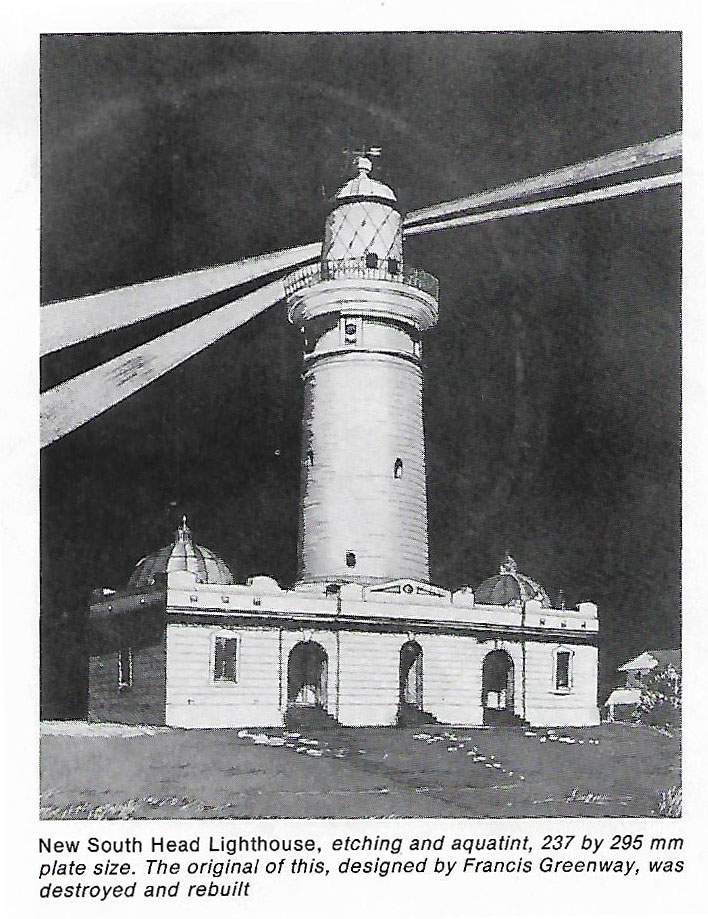

The thirteen prints in the Greenway Suite are both the artist’s tribute to Francis Greenway and to those other etchers of an earlier generation who first made us look at our architectural heritage. Before starting to think of individual prints she re-read Lionel Lindsay’s book on Sydney Ure SMITH Old Sydney Etchings, and started to compile a massive folder on Greenway and the buildings grouped around Queen’s Square. These notes start with a quotation from the Australian writer Ruth Park:

Francis Greenway wore ill luck like an old shirt . . . the things that happened to that man! His eldest son drowned, dogs bit him, footpads bashed and robbed him, his wife died, he was driven from his house. Ruined and miserable, he died in 1837, and is buried in a grave now forgotten.

Yet Greenway is the architect who more than any other person created what we think of as New South Wales colonial architecture.

Griffith has moved these old colonial buildings into present time, away from their colonial origins or later picturesque interpretations. So in these etchings we see that tradition of the classic Georgian proportions and the old Queen in her square; the harsh architecture of the past decade interrupts any inclination to romance. It is probably best described as Old Sydney without the sentiment.

To achieve her large scale clean line effect Griffith has adopted modern techniques to these very traditional subjects. Getting up very early in the morning, to avoid the ubiquitous motor car, she took black and white photographs of both general and detailed views of the buildings. Later some of these details, including the intricate patterns of convict brickwork and leaf patterns, were transferred to the etchings using a photosensitized ground. In other prints photographs were amalgamated to experiment with different perspectives. The total effect of this series of etchings is of variety and energy combined with disciplined lines and subtle perceptions.

Griffith’s work is seen at its best in the print of the New South Wales Barracks. It is dominated by the aggressive figure of Queen Victoria whose harsh weathering is emphasized by the coarse aquatint treatment of the base. This was achieved by lightly spraying the surface with a pressurized can of household paint. This is a contrast between the harshness of this figure and the fine grain aquatint on which it stands. The Queen looks as though she is commanding her subjects, the pigeons which are the curse of old buildings and her figure is thrown into sharp relief by the stormy sky, achieved by roughly painting over the plate with acid resist and letting the acid freely bite into the gaps.

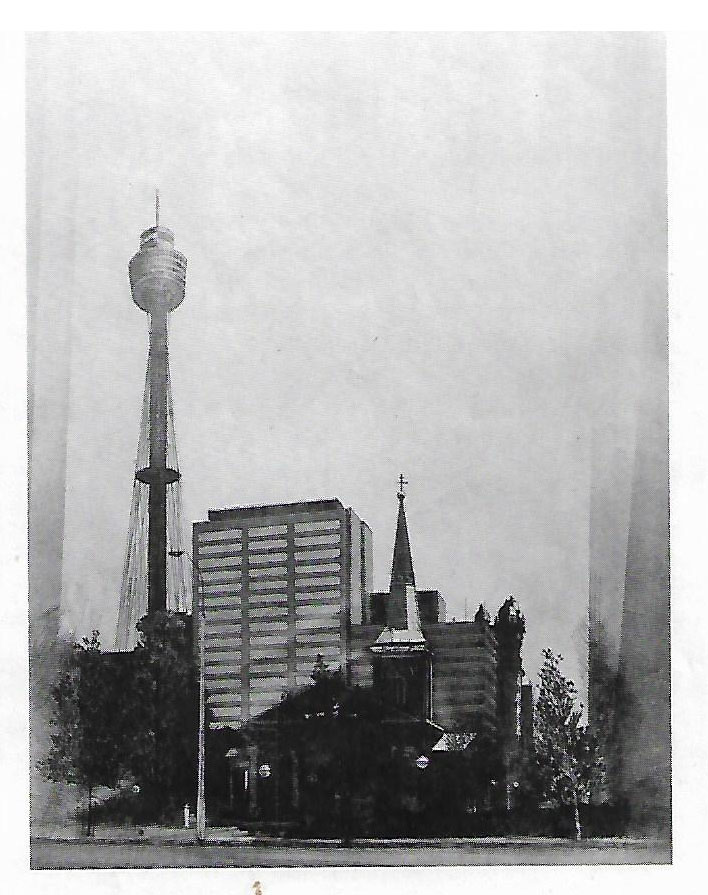

By way of contrast, Queen’s Square is a refined, highly stylized pattern of acute angles and subtle gradations of tone in fine grain aquatint. The subtle modeling of the shadows which frame the central image give this print an almost tactile quality, as though the paper were embossed rather than inked. The classic symmetry of Greenway’s St James’ Church is counterpointed by the aggressive blocky structure of the new St James’ center with its glossy windows massed behind the older building.

Above all the soaring point of the Centre point Tower, a symbol of mass consumption and the power of money, serves to throw into relief the quiet restraint of the church spire.

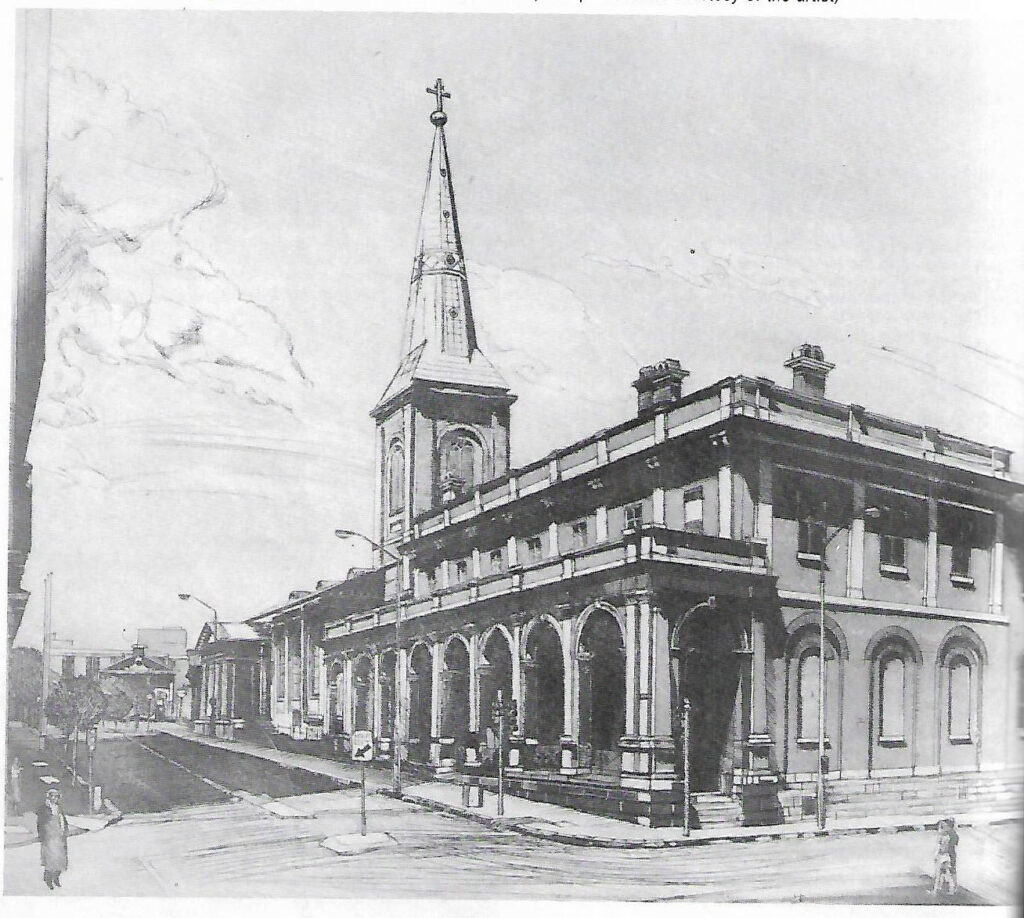

The formal relationship between the angles of old and new buildings is also important in The Supreme Court. Here the jutting projection of John Verge’s portico on St. James’ Church balances the classicism of the Barracks in the rear, and halts the flow of the continuous arches of the court building. The possibly archaic impact of this Georgian street is prevented by the 1980s casual clothes of the couple strolling across Elizabeth Street and the shadow of the aggressive Sydney University Law School building.

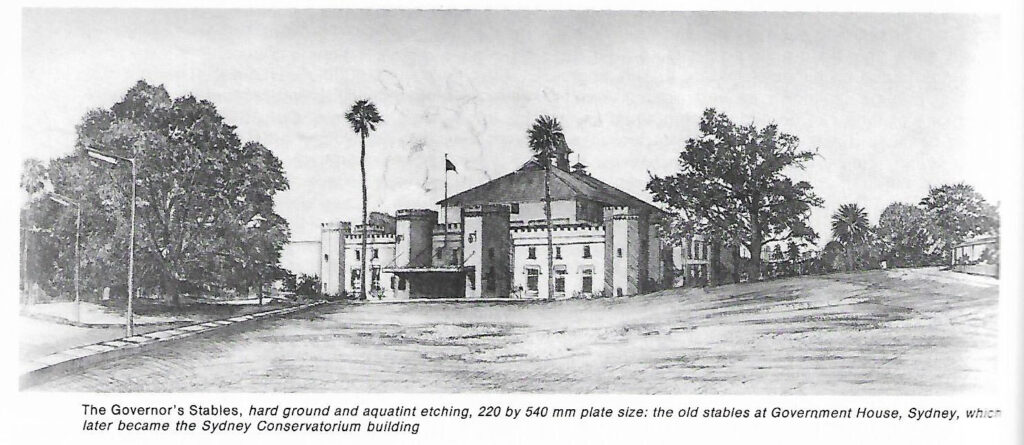

The order of this print, ruled by traffic lines, is emphasized by the eccentric clouds which almost appear to float from the School itself. A variant on these clouds is used in the etching of the Conservatorium of Music, Greenway’s Gothic folly executed at the whim of Mrs. Macquarie. These onetime stables, placed in their garden setting, are given rhythm by the judicious placing of modern lamp posts and trees.

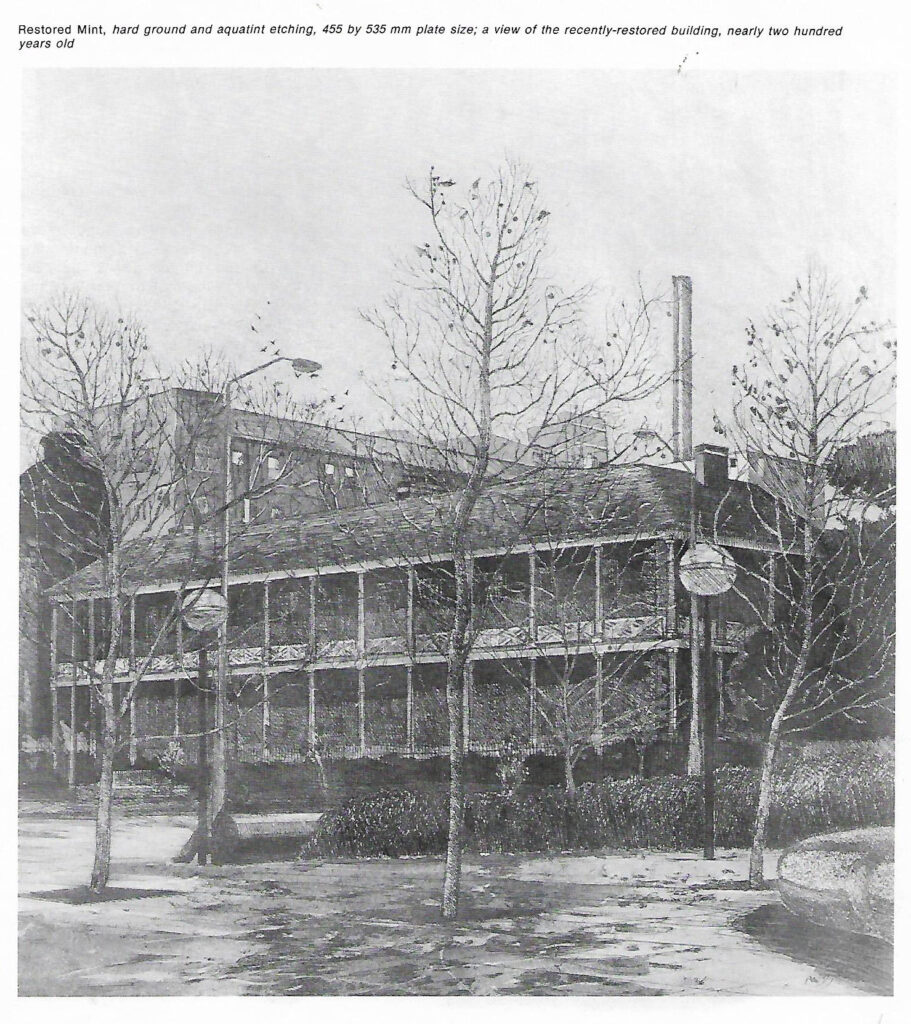

The old Mint Building, part of the new Museum, which opened at the end of October, was not designed by Greenway. Rather, almost his first task in the Colony was to condemn it soundly for faulty construction and lack of classic proportion. But he did correct many of its faults and the building remains today a rare piece of pre-Greenway architecture which still has a certain naïf charm. Griffith’s two prints of this part of the new museum are more restrained, using the traditional techniques of etching to create a light charm, and balancing this with open bite (a more modern technique) in the seats in the foreground. and

These etchings, Griffith’s major printed work to date and the first published as a complete suite, show the etcher at the height of her technical achievement. The skill which she has brought to aiding the work of other artists is here seen in her own individual treatment of some of the favorite traditional subjects of Sydney artists.

Leave a Reply