Go thither, some of you, and take his gold:- The rest forward with execution.

Away with him hence, let him speak no more.

I think I make your courage something quail.

When this is done, we’ll march from Babylon,

And make our greatest haste to Persia.

These jades are broken winded and half tired;

Unharnessed them, and let me have fresh horse

So; no their best is done to honor me,

Take them and hang them both up presently.

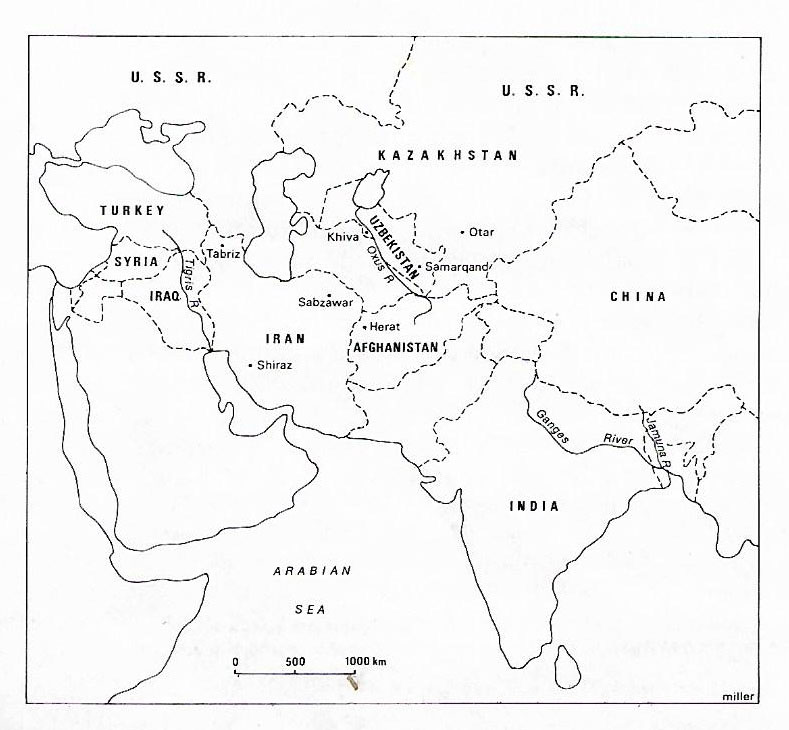

In ancient and medieval times Iran and India were constantly invaded by ambitious adventurers from Central Asia. Genghis Khan was one of these conquerors. After his death in 1227, his four sons divided their own right. His second son Chagatai (1227-41) ruled the land stretching eastwards from Transoxiana (roughly modern Uzbekistan) to eastern or Chinese Turkestan. Of Chagatai’s descendants, Mubarak Shan (1266) was converted were pagans and Buddhists. The Raglans clan of the Chaghtayids, however, remained Muslim. It was to this clan that the great conqueror Tamerlane belonged.

Tamerlane was born in 1336. He quickly mastered archery and horsemanship and, although he could neither read nor write, he was fluent in both Persian and charlatan Turkic conversation. His father died when he was twenty-five years old and Tamerlane rose to power dint of his own merit. An arrow wound from a war in 1363 made him permanently lame. In Persian he came to be called Timor Lang (Timor, the lame). The Anglicized form is ‘Tamerlane’ but Christopher Marlowe has popularized ‘Tamerlane’ but Chris toper Marlowe has popularized ‘Tambour-laine’.

In 1370 Tamerlane ascended the throne with full Mongol ceremony; the noblemen and lords who prostrated themselves before him, called him ‘Emperor of the Age’, ‘Conqueror of the World’, ‘Lord of the Fortunate Conjunction of the Planets’. The military forces, which served as his instrument of conquest, were primarily nomadic – mounted horsemen skilled in archery. They were Mongol-Turkic in origin but were also called Tatars or Chagatai. After his coronation Tamerlane fortified Samarqand and made it his capital.

Tamerlane believed that by Divine Decree the whole world was subject to his power and that God had given all its countries over to his rule. Fortunately for him, no powerful ruler was left between the Oxus and the Tigris and the Ganges and Yamuna to thwart his ambitious plans.

First Tamerlane consolidated his power around Transoxiana. Then, between 1381 and 1392, he conquered Herat in modern Afghanistan and invaded southern Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. He spared only Afghanistan and invaded southern Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. He spared only the artisans and craftsmen whom he employed to make Samarqand the unique capital of the world. At Shiraz in Iran, the Persian poet, Hafiz is said to have been taken to taken to task for writing the following verse:

If that unkindly Shiraz Turk would take my heart within her hand, I’d give Bukhara for the mole upon her cheek, or Samarqand.

Tamerlane asked Hafiz how he dared suggest exchanging Samarqand or Bukhara for the mole upon Shiraz Turk’s cheeks when he (Tamerlane) had laid waste thousands of cities and countries in order to embellish Samarkand and Bukhara. The poet replied that it was his own prodigality that had impoverished him so terribly. Tamerlane dismissed the poet with a smile and suitable rewards.

Between 1392 and 1396, Tamerlane conquered the northern regions of Iran and seized towns in northern Iraq; then he overran South Russia. In 1398 he invaded India with lightning speed, sacked Delhi and returned to Samarkand via Meerut and Jammu. Besides amassing enormous booty, Tamerlane Took many Indian artisans and craftsmen with him. Between 1399 and 1404, he carried fire and sword into Georgia, Syria and Turkey. On 18 February 1405, however, Tamerlane died at Otter, in what is now Soviet Kazakhstan. His final objective, which death had frustrated, had been the annihilation of the Ming dynasty of China.

Tamerlane, following his Mongol predecessors, wanted to have his exploits recorded in over-drab-matised histories. The earliest work was compiled by an Iranian scholar from Tabriz in northern Iran. It is entitled The Book of Victories, the Zafar-nama. Another Iranian, Sharfu’d-Din Ali Yazd, a favorite of one of Tamerlane’s sons, wrote another more detailed Book of Victories (Zafar-nama). It was completed in 1424-25 and is more popular. It does not conceal the fact that in Sabzwari (eastern Iran) Tamerlane had a tower constructed out of two thousand living men, who were piled on top of each other and commented together with bricks and clay. In Turkey, four thousand of the Armenian defenders of the town were buried alive in fulfillment of his promise that no blood would be shed if they surrendered. At Isfahan, in Iran, seventy thousand heads were piled up to make a pyramid. Interspersed with Qur’anic verses, the passages of Zafar-nama declare ad nauseam

The real character of His Majesty was inclined to justice and the promotion of prosperity of the people and the object of his high ambition was the building up of territories. The error displayed and the destruction wrought occasionally by his world-conquering troops was due to the necessities of conquests, countries cannot be annexed without hutments and the establishment of prestige.

Tamerlane himself, however, believed that he was the destined scourge of God. Rightly Christopher Marlowe concludes his play,

Farewell, my boys! My dearest friends, farewell!

My body feels, my soul doth weep to see

Your sweet desires deprived my company,

For Tamburlaine, the scourge of God must die.

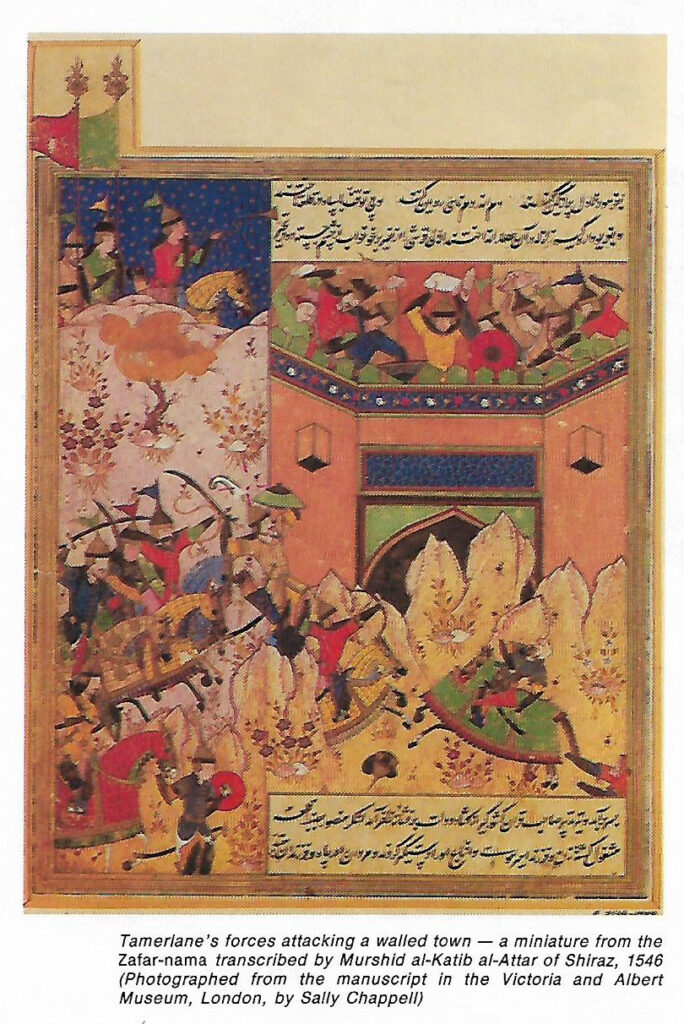

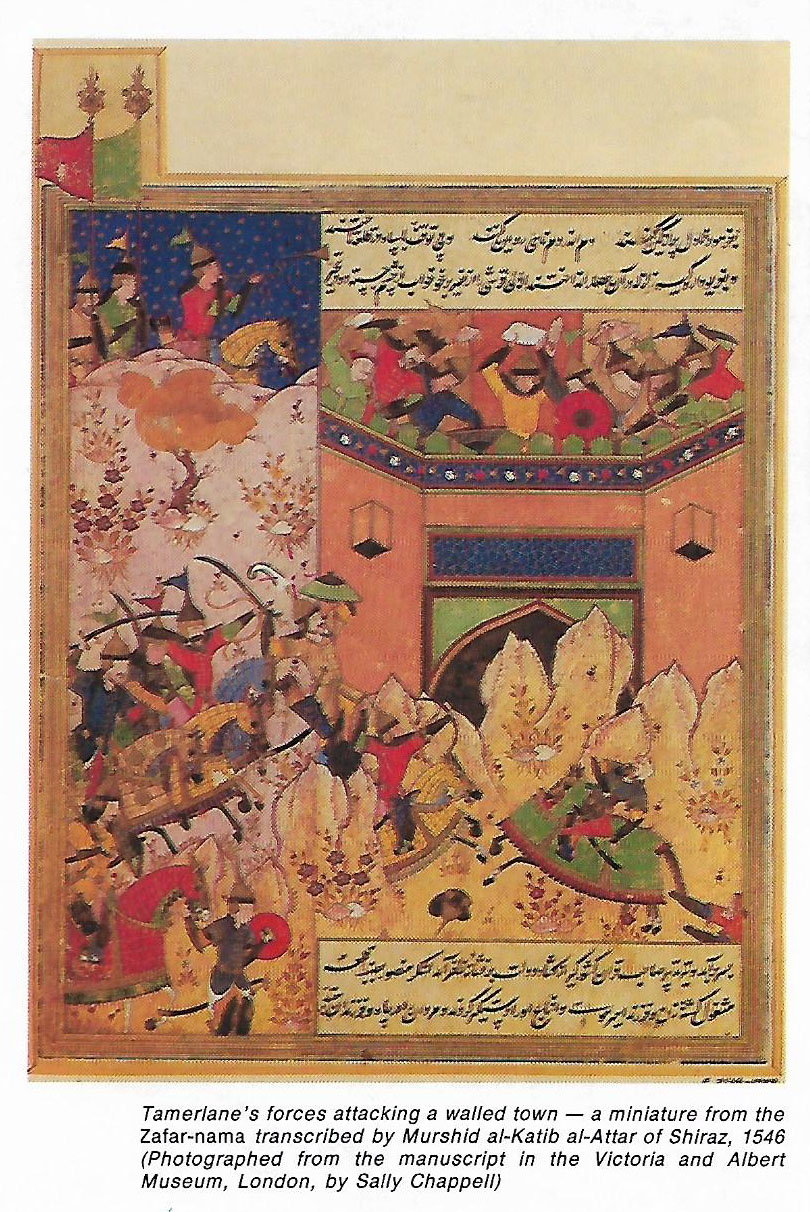

Several copies of the zafar-nama were beautifully illustrated. A copy in the Victoria and Albert Museum, transcribed by Mushin al-Katib al Attar of Shiraz in 1546, contains fascinating illustrations by Iranian artists. A miniature painting (illustrated) depicts the storming of a walled town which is being defended by the garrison. The victorious army is poised to enter the town. The coloring, in the cool range of low-toned blues and yellows, is lovely sixteenth century Iranian brush work. It is pervaded by lyrical notes but Tamerlane’s vigor in action is not lost.

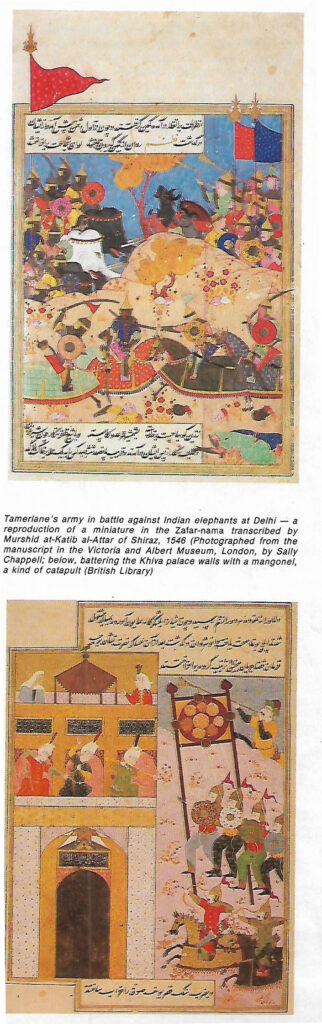

A miniature in the same Zafar-nama shows the Indian army of Delhi defending their city against the lightning-like attacks of Tamerlane’s army. The elephants in the Indian army were the thanks of those days and Tamerlane’s army was stricken with panic. Tamerlane however, remained steadfast and the full charge of his vanguard turned the elephants towards their own army. In their fury they trampled their own forces. In the illustration the painters have portrayed the dynamism of the Mongol attack.

A copy of the zafar-nama, transcribed by the same Attar (Add. 7635), exists in the British Library, London. The painters also belonged to the Iranian school which had illustrated the Albert Museum Zafar-nama. The scene depicted below is most instructive. It deals with Tamerlane’s invasion of Khwarizmi (Khiva in modern Uzbekistan, U.S.S.R.), which was ruled by Yusuf Sufi, in 1373. Yusuf also belonged to the Turkicised Mongol dynasty of Khwarizmi which united the Mongol Golden Horde and the Chagatai tribes. Tamerlane’s army had erected a mangonel to batter the walls of Yusuf’s place before taking it by storm. The scene differs from those depicting resistance at the forts; here the inmates realistically betray their anxiety at the fall of the palace.

Tamerlane’s career was given a romantic touch by the eminent poet Abdullah Haiti, a nephew of the famous Persian poet and mystic Mililani Neruda Din Abdurrahman Jami (d.1492). Hatifi’s book is known as the Timur-nama or the History of Timur (Tamerlane). In it the chivalric ideals of epic poetry were sacrificed at the altar of the lyrical attitude with its underlying psychological emphasis.

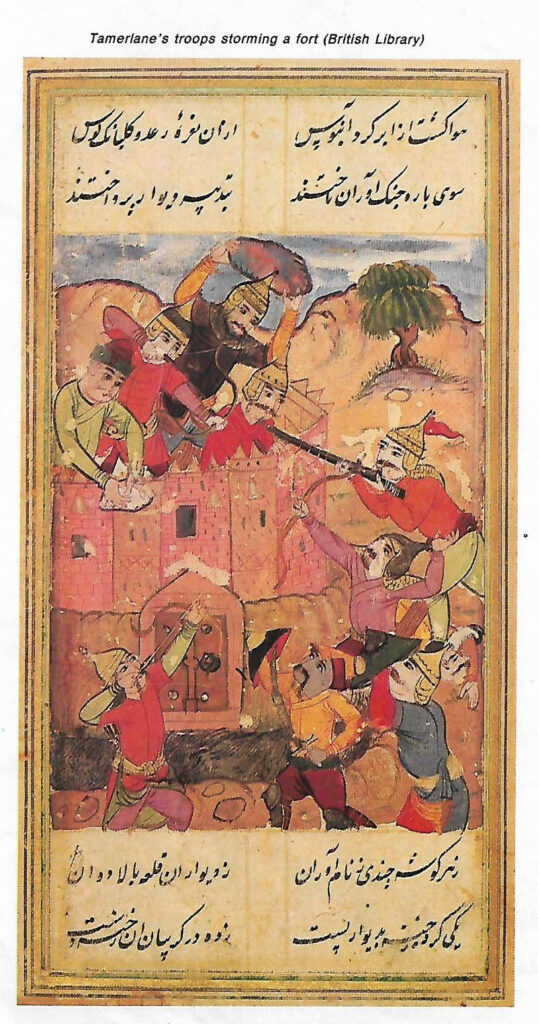

The copies of Timor-nama were also illustrated. The copy in the British Library London, (ADD.7780) was transcribed in the early seventeenth century. The artists were not of a high standard and were ignorant of the tactics of storming forts. Tamerlane’s soldier fires a matchlock which was not then known in this part of the world for it was in use only from the early sixteenth century onwards. Such anachronisms are quite frequent in later paintings. Nevertheless the action on both sides is vigorously portrayed.

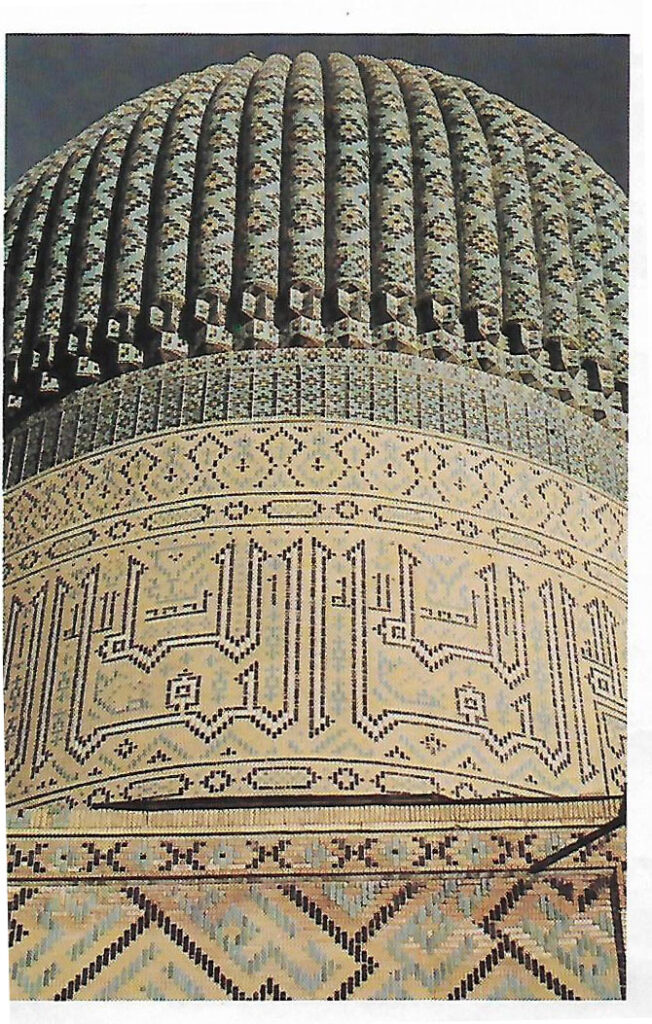

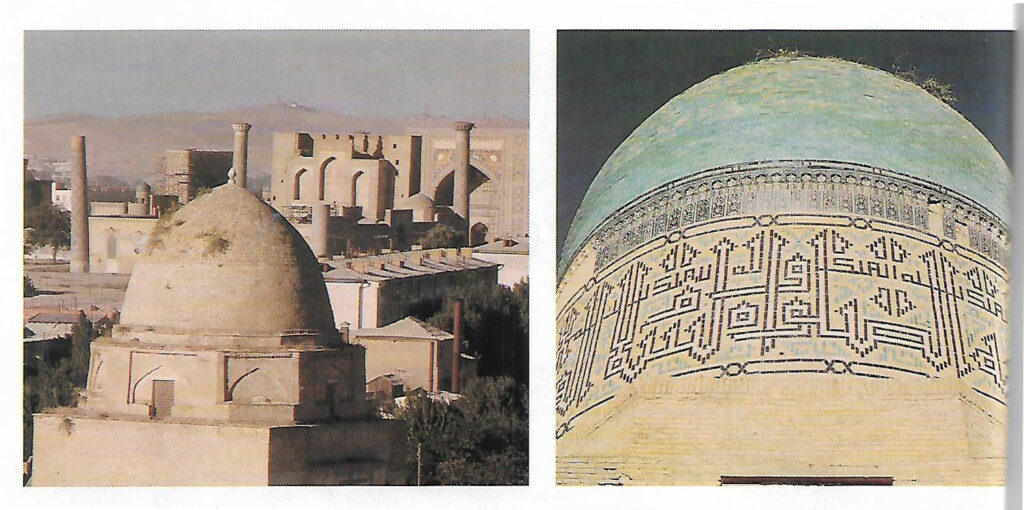

Tamerlane ordered his architects to build monuments with the same haste as he exhibited in his conquests. Their main characteristic was ostentation, illustrated by the size and decoration of the monuments. The experts in mosaic work brought from Isfahan, Kasha, Yazd and Karman in Iran to Samarkand and Bukhara filled the monuments of that region with color and beauty. In 1402, Tamerlane built a mortuary for his favorite grandson, Mira Muhammad Sultan, who had died fighting in a foreign country. Tamerlane was also buried there after his death. Externally this enormous tomb was an octagon but later two minarets, joined by a façade, were added outside the main entrance. The turquoise of his thirty-four-meter dome descends from their common apex with a sharp turn downwards to join the blue drum with its vivid blue lettering. It is called Guru-I Mir. It set a pattern for many future domes but none equals it in beauty and strength.

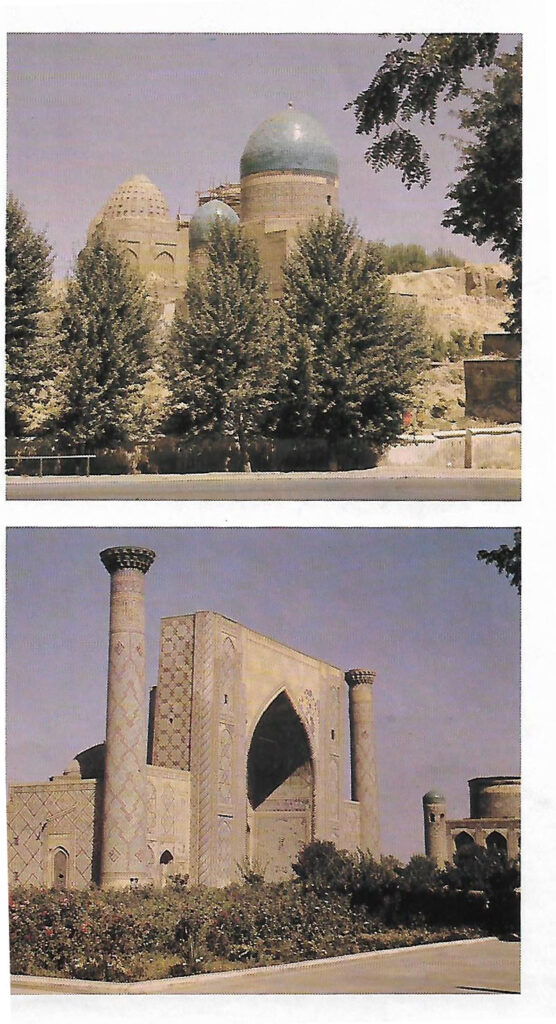

The carved stone frieze in the interior of the tomb seems to have been worked by the Hindu Sculptors whom Tamerlane had transported to his capital. When he returned from his Indian campaigns in 1399, Tamerlane built a new mosque to replace the one in Samarqand as a token of his thanks to God for victory. The complex, however, is known as Bib Khan am, who is said to have been one of Tamerlane’s queens. Its long drum and blue dome dominate the whole area. The rectangular vaulted halls are now being restored.

Politically, the reign of Ulugh Beg, one of Tamerlane’s successors (1447-49), was insignificant but culturally it was brilliant. He encouraged fine art and took an interest in astronomy and mathematics. His observatory in Samarkand still survives. On the west side of Regis tan (an enclosed square in Samarkand, some seventy by sixty meters) Ulugh Beg built a madras or seminary. On either side of its arched, mosaic gateway are rounded minarets, ornamented with diagonal bands of beautiful calligraphy. Set behind this façade are square rooms at each corner and small rooms on all four sides.

Another imposing mausoleum also contributes to the beauty of Registan.

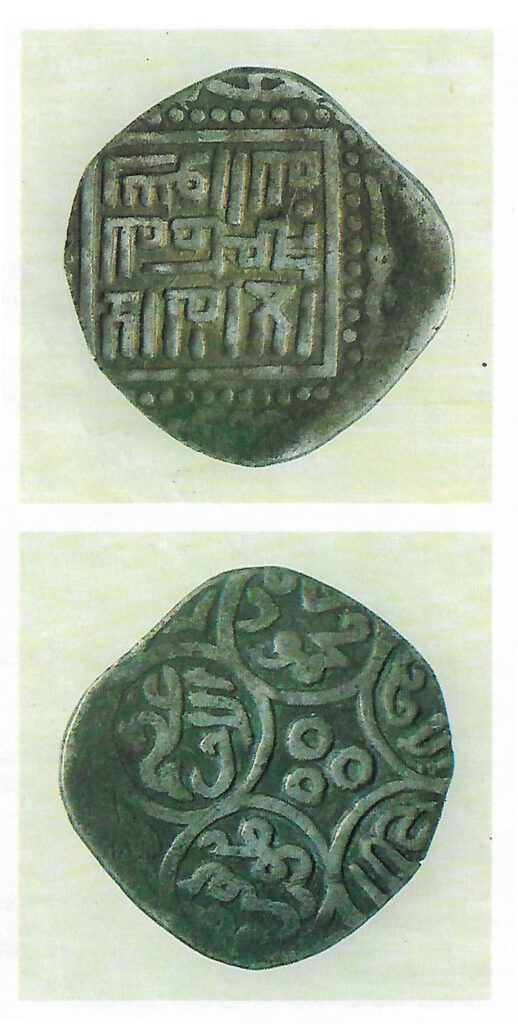

The cemetery containing Tamerlane’s descendants lies within the holy precincts of the Shah-I Zenoah. The title (The Living Prince) belongs to Durham, son of al-Abbas bin Bad al-Muttalib, a cousin of the Prophet Muhammad. Durham died in 676 while fighting the heathen nomads in the region and was buried in Samarkand. The people there often visit his tomb believing that he had not died but was still living. Even during the Mongol domination of the region, visits to Shah-i Zenoah did not decline. The present Soviet rule has also not affected the stream of pilgrims from distant areas who throng there wearing their colorful village costumes. They prostrate themselves at Shah-I Zindah’s grave, as well as at those of the princes and princesses of Tamerlane’s family, believing that their wishes will then be granted. The Shah-I Zenoah complex was also built by Tamerlane’s architects and its imposing portal was erected by Ulugh Beg. Tamerlane’s coins also exhibit impressive calligraphy and design. They reproduce the Islamic credo in varied styles.

Leave a Reply