AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL AND CONTEMPORARY WESTERN

ACCORDING to Lewis Mumford, historian of the transition from ancient to modern society:

‘The clock, not the steam engine, is the key machine of the industrial age.’

While not everyone would concur with this, there does seem to be widespread agreement that it is our view of time which most distinguishes us from previous cultures:

‘The most fundamental dividing line between modern, industrialized societies and traditional, non-industrial ones appears to lie in the value accorded to time as such’.

speed, tempo, precision and other concepts are of little concern to pre-industrial people . . .In these temporal phenomena of modern society we have a situation unique to our time’.

‘. . . The haste and rush which characterizes our life are something typically modern’.

While a nostalgic leaning towards pre- industrial modes of living in counter- culture circles has helped some to begin appreciating earlier styles of life, most urban dwellers in modern cities would find it hard to understand how unimportant time can become in a non-industrialized, non- western setting. A comparison of aboriginal and western attitudes towards time brings out the sharp differences that exist.

For the Australian Aboriginal it is chiefly the cycle of seasons that makes certain times important, and provides the clue as to what should be done within them. Rather than time being a primarily linear affair, progressing from some point in the past to another point in the future, for them it follows the annual rhythms of nature. Apart from the horizon created by the immediately- coming seasons and the expectations associated with them, there is little interest in the future or in extending one’s present experiences of time into it. The past, viewed like the not so- faraway ‘olden times’ of children, is a repository of wisdom and skill. As for the ‘Dreaming’, that mythical dimension of life which dominates and permeates all traditional Aboriginal thinking, that is ‘independent of the directorial flow which characterizes everyday life’. And to that extent seems ‘independent of the importance placed on past and future’.

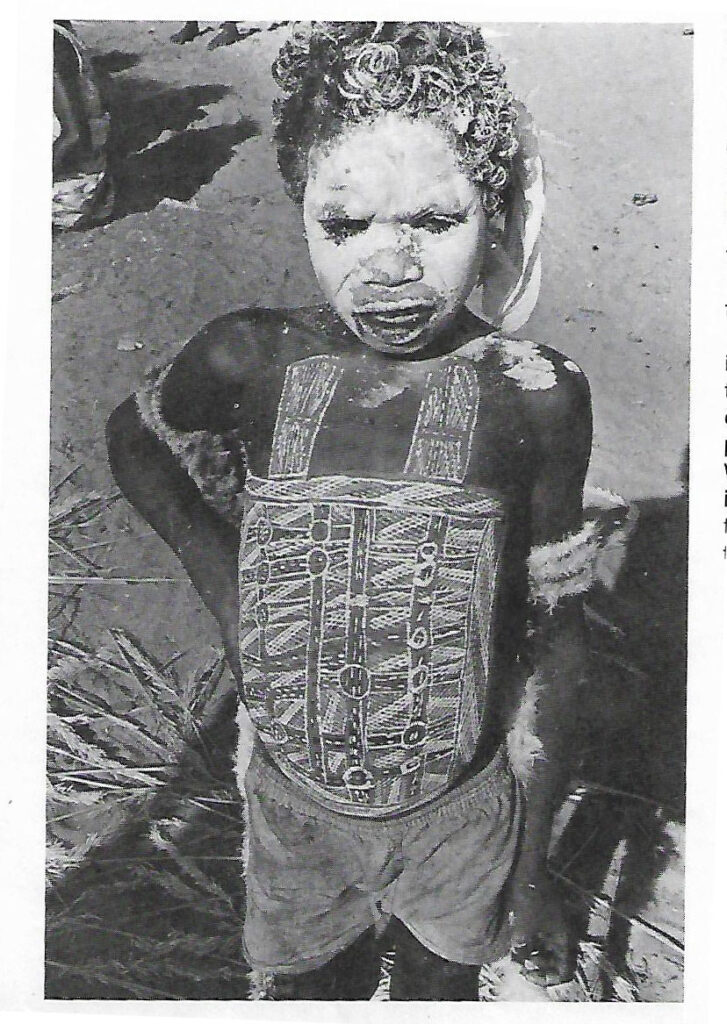

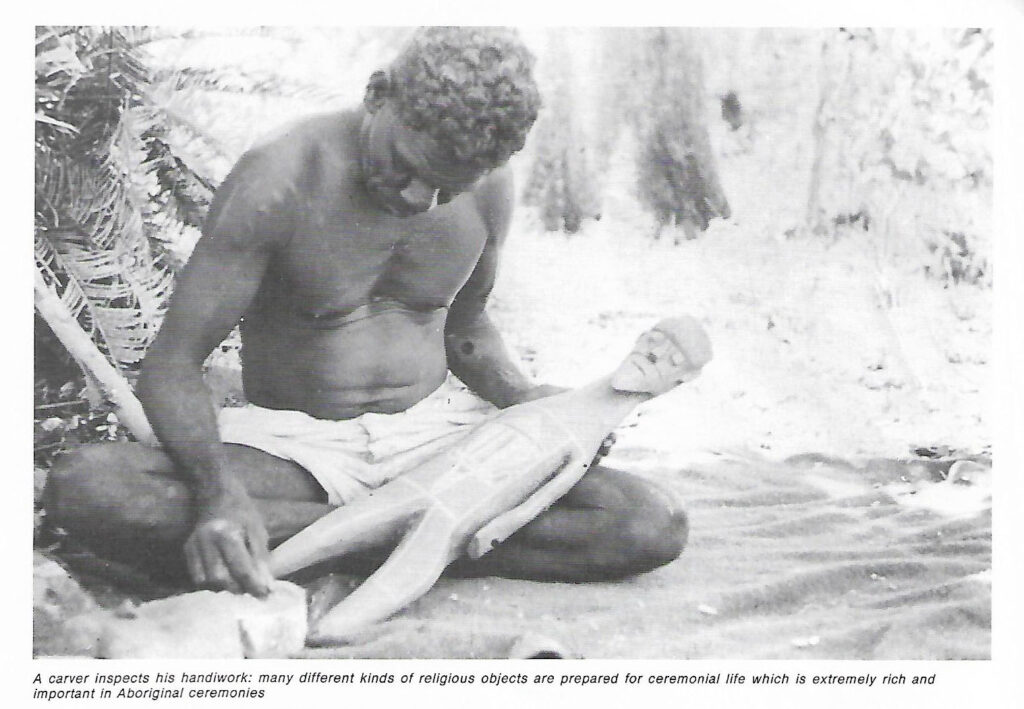

Much more attention is given to the present with its practical daily concerns. Ceremonial rites orient themselves to the present as well, sanctifying and empowering it rather than fixing attention on the past or propelling the participant into the future. Within this present, activity and non-activity alternate in a quite regular way, governed by the rhythms of the natural world. No distinction is drawn between them in terms of the value of the time spent. Unhappily this differing approach to time is fundamental to many problems and misunderstandings in Aboriginal/white Australian inter – relationships. Aborigines are frequently labeled as lazy and unreliable because they lack the conditioned response to the demands of lineal time upon which western society has patterned its life.

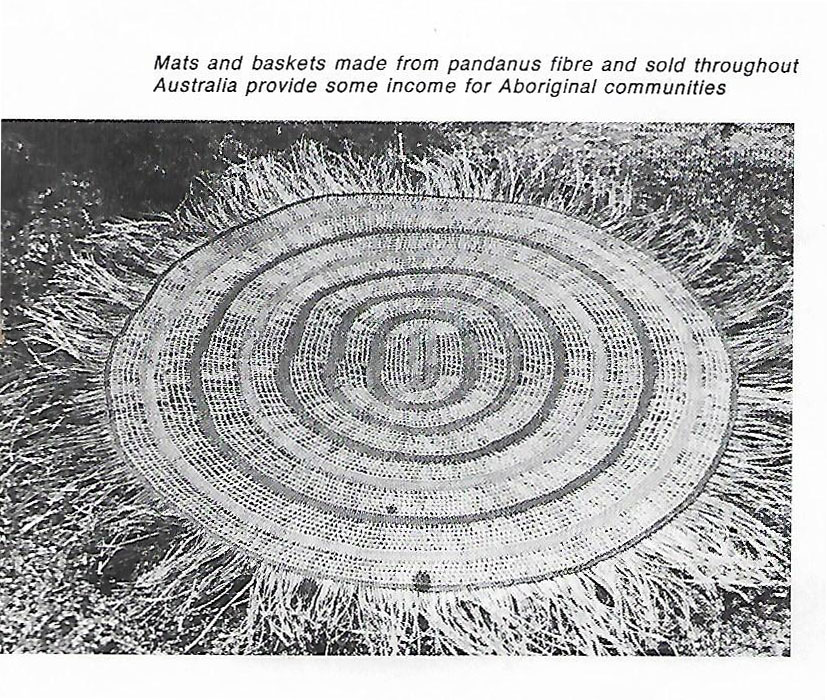

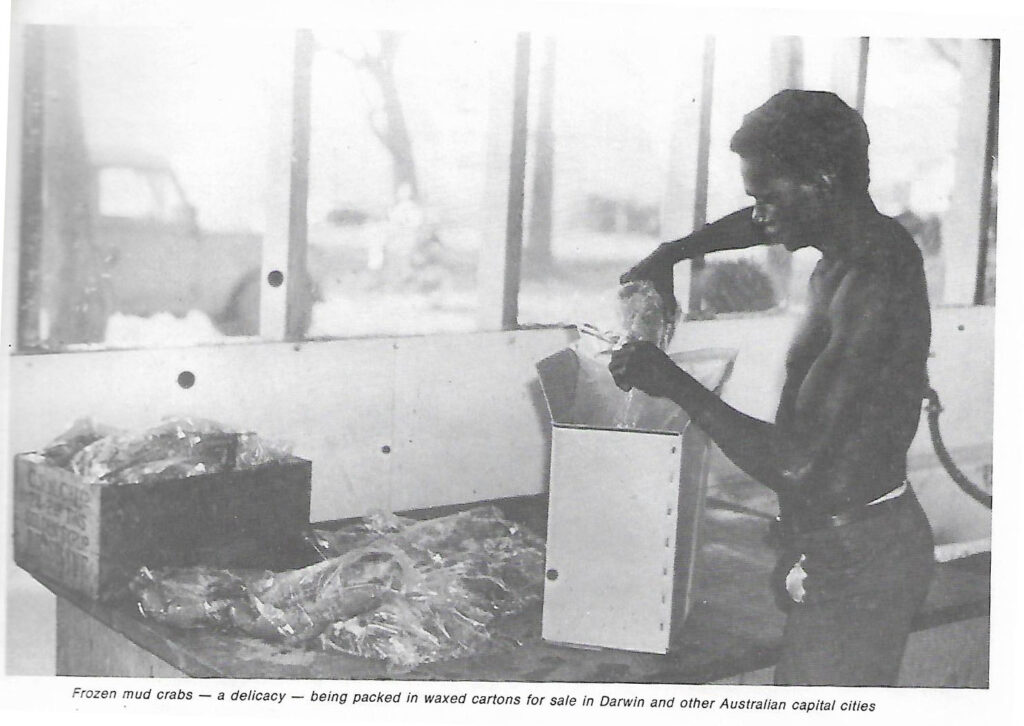

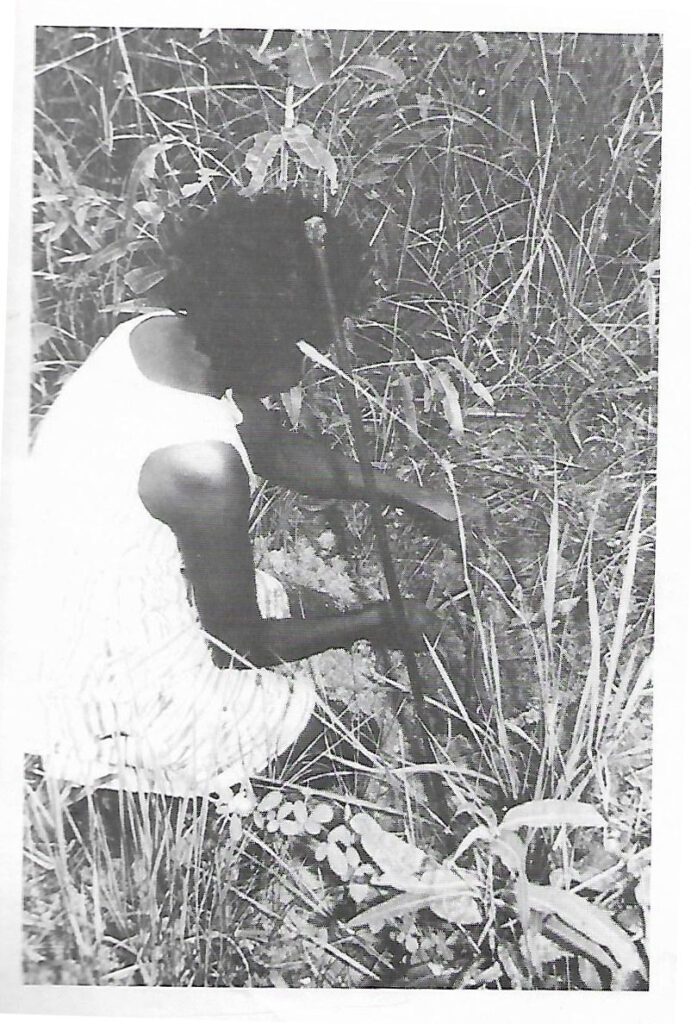

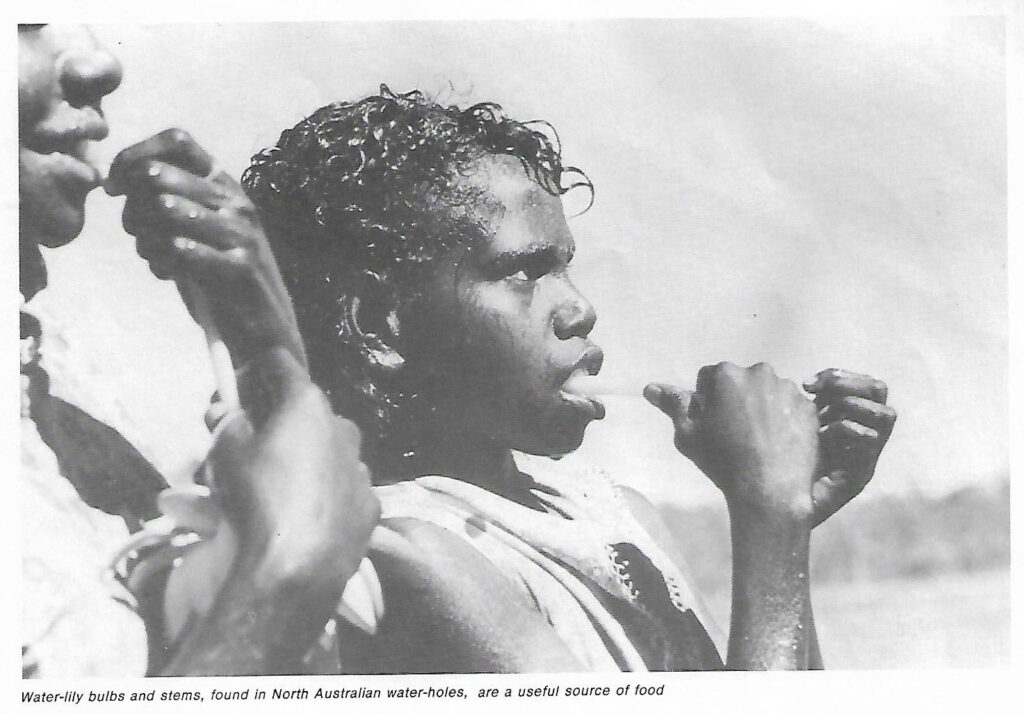

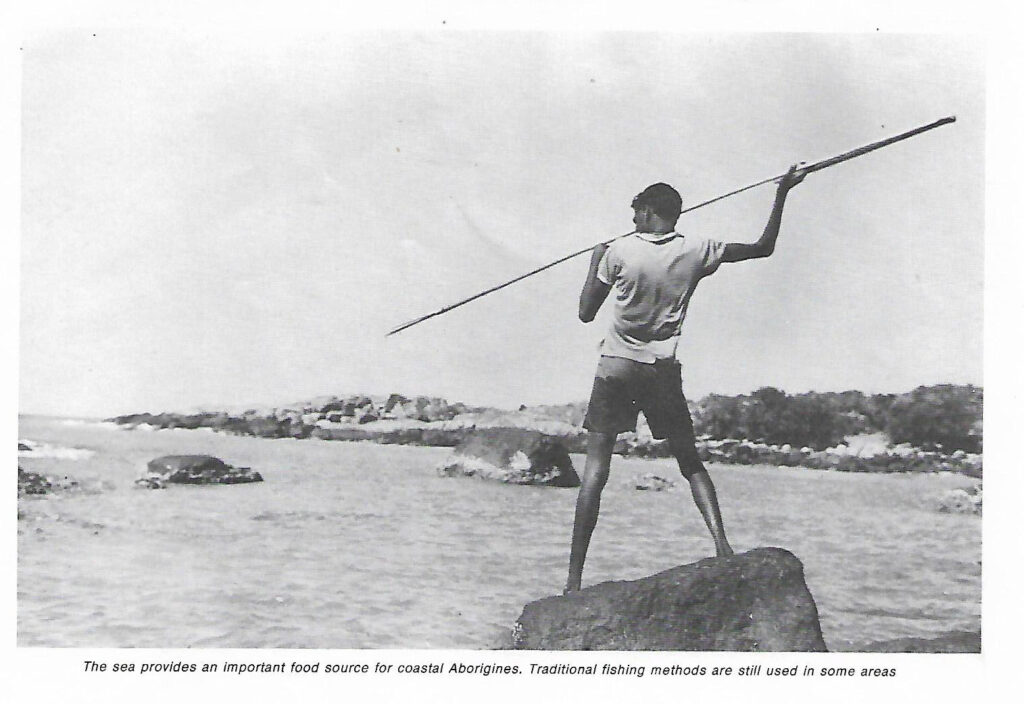

In the main, Aboriginal people have no need to measure time accurately, nor carefully program its use. For them everything has its own natural time and pace. This can be marked quite satisfactorily in less specific ways than we employ. One reason for this is that Aboriginal people are not ‘goal-setters’ in the way we are. Goals pertain to the future and make us more conscious of the length of time between setting and achieving them. It is interesting in this connection to note that Aboriginal tribes for the most part have never even planted and harvested in the strictly European or Asian sense. Another reason is that Aboriginal people – particularly those with few outside links for essential items and practices-basically spend their lives in one ‘space’, although there are excursions into the territory of other tribes; Europeans tend to move through a number of social contexts every day which can only be negotiated through temporal coordination. In an Aboriginal tribe regular contacts need not be governed by time because tribe members see one another daily. Plans need not be made for the external rhythms of nature, and the broad relationships in the kinship system determine what one does in time.

The important thing is for the individual and group to fit in with the natural and social necessities, and for time to take its quality from the activity -or inactivity-in question (Interestingly enough it is the women who are more often the key timekeepers: given the fact that the monthly cycle. So, the various Aboriginal groups sensibly adapted weapons, chattels and the institution of property to these basic conditions. They also shaped ordinary activities like socializing, trading, celebrating etc. so as to accommodate their mobile-rhythmical world.

In contrast with the Aboriginal attitude towards time our modern view is strongly linear in character. The west is deeply indebted to Jewish and Christian approaches to time here, for the idea of time moving steadily from a definite end, with certain novel and decisive events taking place along the way, gave the west its peculiarly forward-looking, dynamic character. This is not to say that Greek Roman thought altogether lacked a sense of progress. Their historians realized that certain kinds of development were taking place, but still within the framework of occasional cosmic upheavals returning most things to the place from which they began. The Judaea- Christian influence, however, is largely responsible for our belief that change, development and reform are possible in social life, our drive towards what lies ahead, and our confidence in shaping and planning the future.

The process of industrialization and secularization over the past few centuries has now led to a more mechanical and exploitative view of time, and to a shrinking of its linear character. Instead of prizing a day because it opens up the possibility of working and relating, giving and receiving, thinking and imagining, resting and praying, each being given its own proper time-we value it for how much can be crammed into it or extracted from it so as to maximize such things as our earnings, our qualifications, our status and our amusement.

It is interesting here to note how much business terminology has affected the way we talk about time. For example, we can earn it, spend it, save it, and waste it. It can be added, subtracted and divided. Time is also measured, bought, and sold. It is indeed our ‘unique resource’. In brief, we have turned time into a commodity-a commodity that is regarded as increasingly scarce and therefore in heavy demand.

Time has also become a highly abstract, mathematical and mechanical affair. The clock watch, or computer – timer defines time for us, dividing it up into small, interchangeable, precise units which can be carefully fixed or arranged. With them we schedule our time, parceling it out to this activity or that, this person or that. The diary, date- pad and calendar also assume increasing importance. They enable us to plan our lives far in advance, to book up time long before it reaches us. In this way pre-packed time, as we may call it, closes its grip more and more tightly upon both ourselves and society. Indeed, it is sobering to consider how much prior programming now enters even into careers and life-planning, let alone commercial, administrative or economic forecasting.

For many people the diary has become most important, and its loss causes the owner himself to feel lost! As for the watch, we become oddly wedded to it in a quite physical as well as psychological sense. How else can we explain the fact that it stays part of us in a way that no other piece of clothing or machinery does-surviving changes of clothing and even undressing? In the strictest sense it has become an extension of ourselves. We all have a heart ‘pacers’ these days, whether we have a heart condition or not! We would also just as surely ‘die’ without them! So, people‘. . . actually became like clocks, acting with a repetitive regularity which had no resemblance to the rhythmic life of a natural being. They become, as the Victorian phrase puts it, “as regular as clockwork”.’

Focusing as closely as we do on the small slots of time that are devoted to different things during the day, and packing as much into a day as possible so that we get the most out of it, we have little time to reflect on what as happened in the distant past, or to look ahead to what may happen in distant future. We tend to feel that the past, whether our own individual biography or history as a subject, deserves attention only insofar as it can be of use. Since it is difficult to draw lessons from it and turn it to present profit, it is irrelevant. Only the knowledge gained from experience that is practically relevant – ‘know- how’ as it is called – justifies consideration of it.

Just as the past becomes reduced to what is presently useful, so the future becomes narrowed to what seems presently practicable. The only future most people and most societies look forward to is what we may term the ‘manageable’ future, i.e., that which can be planned, scheduled and projected from present circumstances. As a result:

‘The more the future is planned, the more it is filled up with activities, wishes, plans and desires, the more it comes to resemble the overloaded present which it was intended to expand.’

In a way, this concentration upon the present, amplified only by ‘know – how’ from the useful past and projection into the ‘manageable’ future, brings us closer into line with the Aboriginal attitude towards time, the main difference being the dominance of mechanical, clock- time in our affairs over more natural and social rhythms. The growing interest in mystical experience and in biological rhythms among some people in the west also accords more with the Aboriginal attitude towards more and the natural world. Other Aspects of Aboriginal life are also attractive to the world-weary western soul, e.g., the greater accord with natural cycles. The regular alternation of work and rest, and the less harried pace at which things are done. In these respects, the aboriginal exhibits a more civilized approach to life than his so-called more advanced successors. The development from his own way of doing things to modern society has not all been in one direction.

But we would only be seeing Aboriginal culture through a romantic haze if we did not recognize its real disadvantages. Though it is free from mechanical bondage, there tends to be a natural determinism about this way of life. For all the commendable balance it has forged between human beings and their environment this is such a delicate affair that it leaves little room for choice or variation. Long periods of enforced idleness and mobile existence also partially restrict the development of a fuller personal, social and cultural life. A more dynamic sense of time – past, present, and future- is necessary for this to take place.

We certainly need to place more store on our individual and social past and so develop a more integrated sense of both personality and history. We also need to open ourselves up to more novel and long-term hopes for the future, and so discover the really creative possibilities that the future contains and which the present so desperately needs. If anything, this means a return to the genuine Judaea- Christian tradition, however, must find relevant expression within, though not be fully determined by, the technological civilization in which we now live.

We cannot put back the clock, but with the reminder that Aboriginal culture gives us and the power that still lies inherent within the Judaea- Christian tradition, we may be able to put it in its place. To re- phrase a well – known saying of Jesus:

‘Man was not made for the clock, but the clock for man.’

Leave a Reply