DONALD Friend, who has lived in Africa, in Sri Lanka and for a long time in Bali before setting back in Australia, has had a long career in painting in Australia. He was, also, briefly a war artist towards the end of the second world war after having been what he calls ‘a hopelessly inept soldier’.

His comment on his war career comes in a recent book, Donald Friend-Australian War Artist 1945 (Currey O’Neill, ISBN 0 85902 344 3) by Colleen and Gavin Fry. Colleen Fry has taught art in Melbourne, while her husband is Curator of post- 1939 Art at the Australian War Memorial, where the works shown in the book are held.

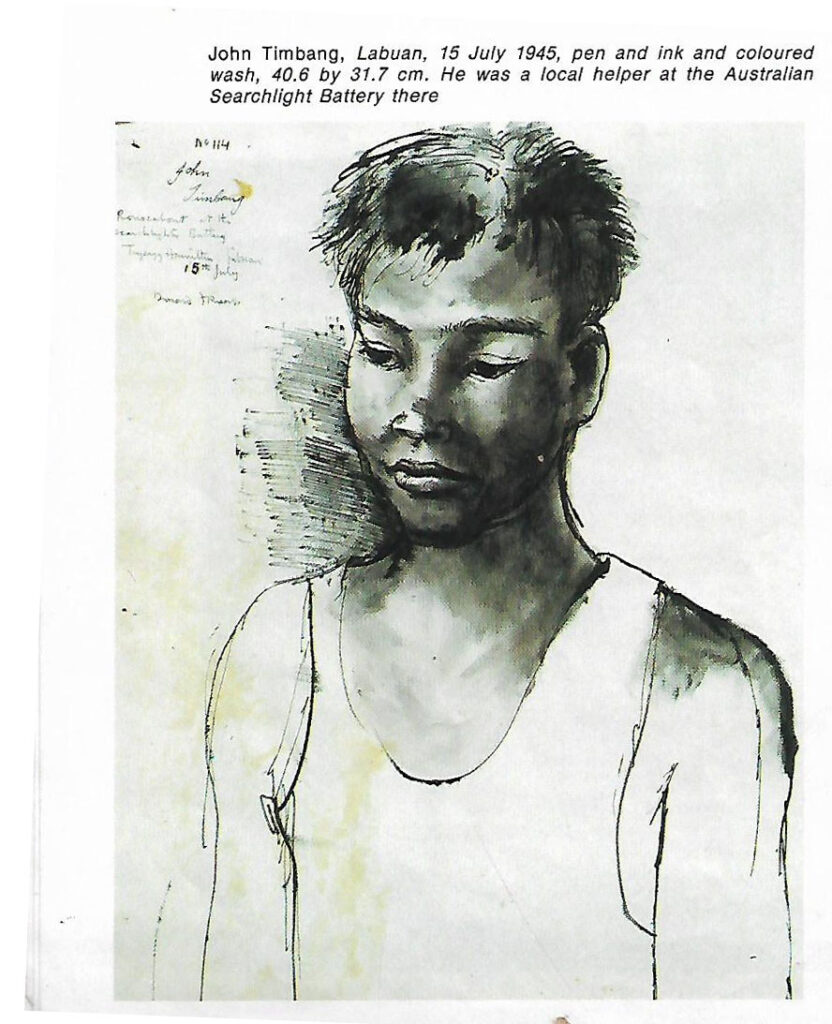

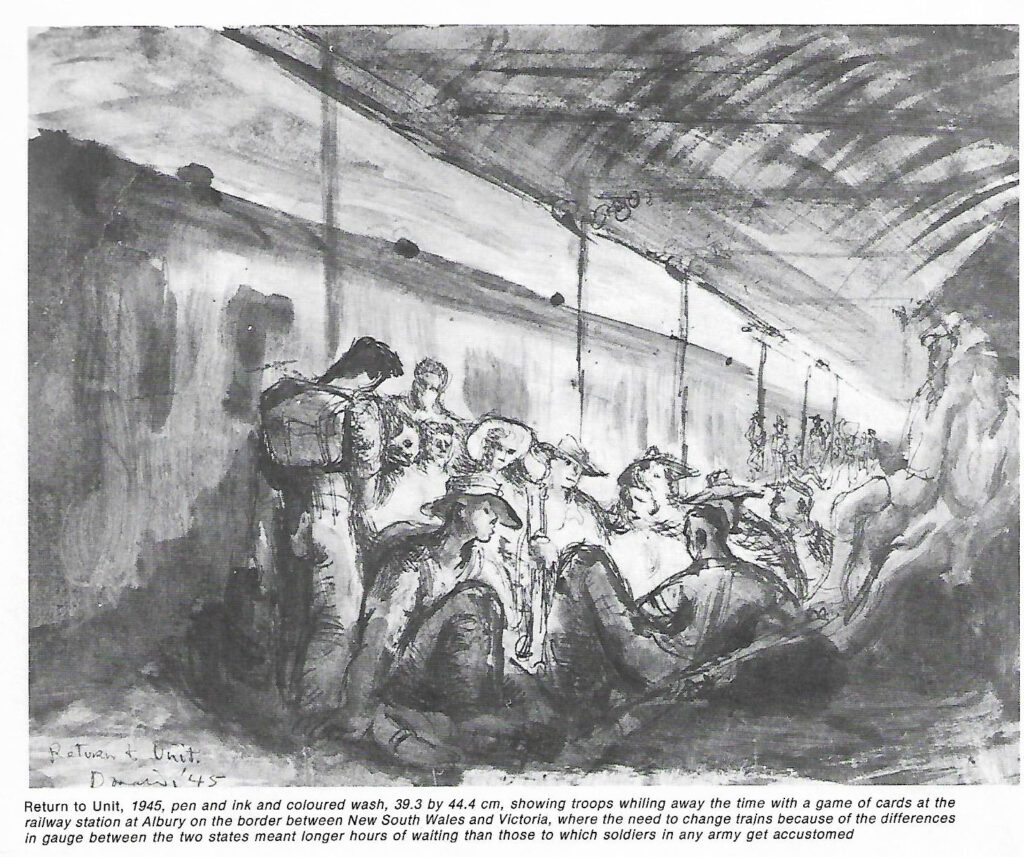

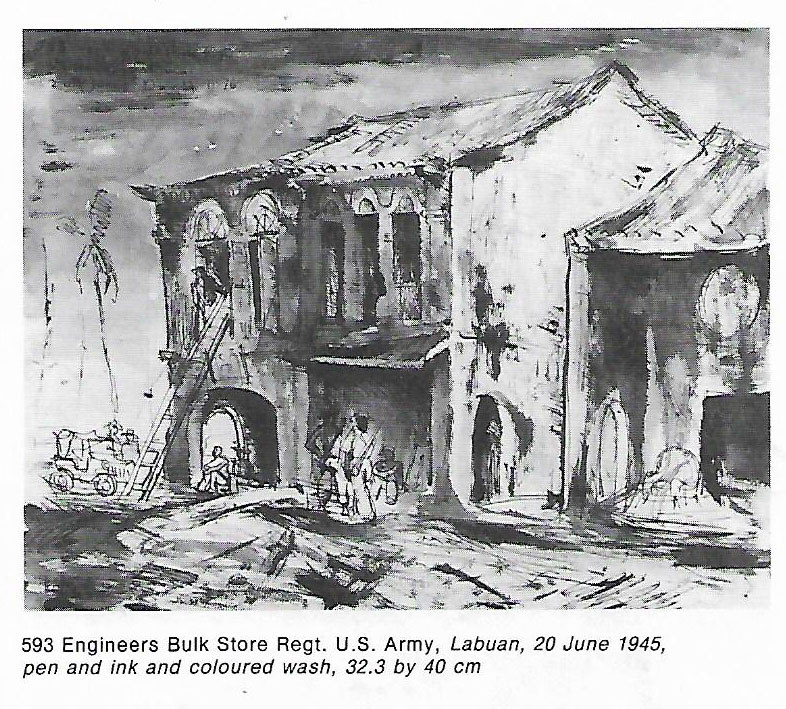

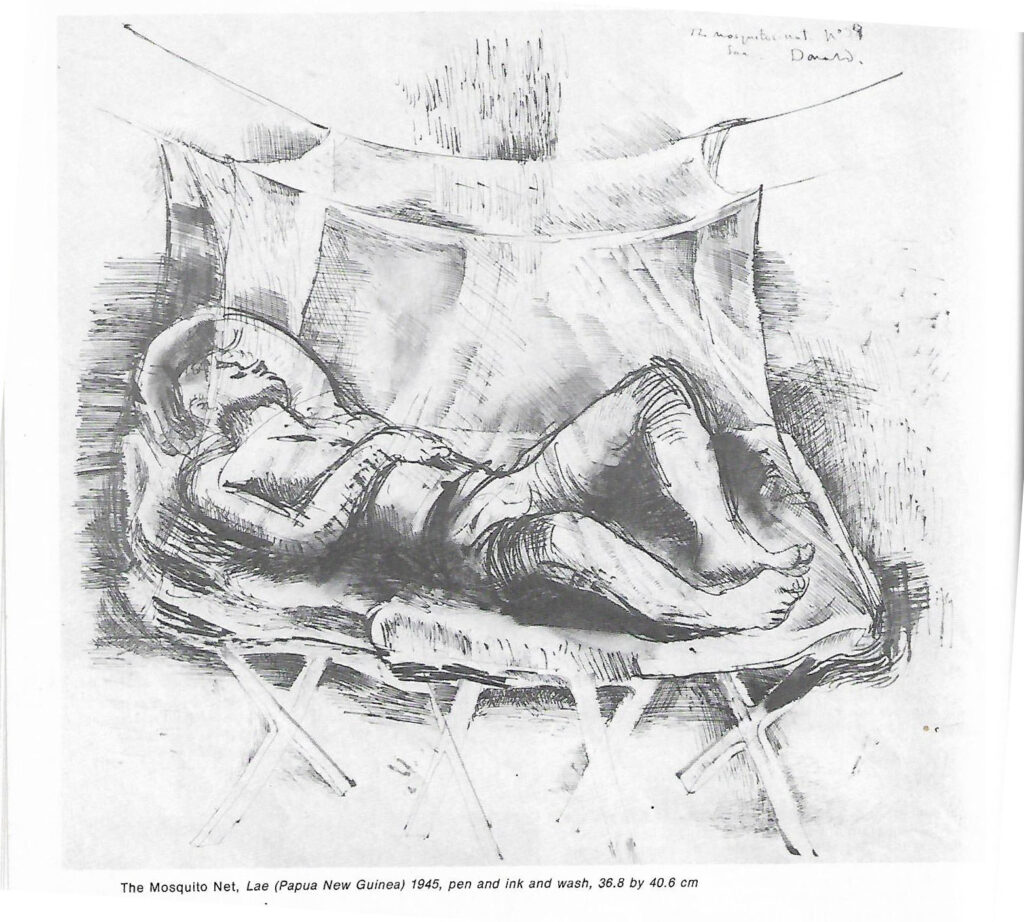

The book is a thorough one: not only are there plenty of the artist’s paintings and sketches reproduced in color and black and white, but there are photographs of areas he covered and an illustrated catalogue of all the works he did while holding commission. The text consists in part of the artist’s own comments on the circumstances in the works were the produced and good background information about him, and especially about his appointment as war artist so late in the piece. To his commanding officer he wrote: ‘The cream of history as I savor it is contained in the individual’s behavior and motives: those oddities, barbarities and nobilities and heroisms seem much more impressible than statistics which tell a dry tale and leave actions devoid of reasons.’

I first saw his work in an exhibition at the old Education Department Galleries in Sydney before the war and the friend with me and I were impressed by their rich color and vigor; she, who had more courage than I, suggested he should asked to do the backdrop for a stage production I was involved in that was fortunately never produced, for the work of a seventeen-year-old could be embarrassing in retrospect. However, he received me kindly, although having knocked on the door of his tiny flats in Elizabeth Bay; I failed to notice the two steps leading down, and sprawled at the feet of the master, manuscript flying. He generously said he would do it, but a transfer and then the war intervened.

Many years afterwards I went to see him in Bali; on the way the taxi-driver said, ‘Tuan Donald – orange baik’, so I realized that he hadn’t changed with success.

He must, incidentally, have been one of the first people in Australia to realize the vigor of African art and brought some back with him from his pre-war stay, which much impressed people in Sydney., although he and some of his fellow- painters known in Sydney as the ‘Charm school’ by the unkind.

It was the Sydney publisher, Urea Smith, who first proposed his appointment as a war artist to Louis McCabe, Art Adviser to the Australian War Memorial, where he had worked during the period between wars, painting the backgrounds to the dioramas, showing, in shop-window style, scenes from battles of the first world war in which Louis Cubin had himself been a war artist before coming back to become Director of the Art Gallery of South Australia. Louis saw more than charm in Donald Friend’s work and recommended him (in contrast to some of the older painters whose work he described as ‘commonplace’) in a letter to Colonel Tremor, director of the War Memorial. He said he had ‘something of the character of Toolkit, a Polish artist the B British are employing as a war artist… I don’t think we want to be too orthodox all the time…’

Interesting is Donald Friend’s relationship with Colonel Treloar, a veteran of the first world war who worked so tirelessly to build up the War Memorial that he lived alone on the premises, seemingly only to leave them when one of his sons came to Canberra in order to have a meal with him at a nearby hotel. Retiring, even dour, Treloar’s relations with his war artists might well be summed up in his comments after Donald had requested his opinions on work already sent down: ‘… my feeling is that he is doing very well, and … I have no doubt that his war pictures will be of great interest to those who admire his work. Although it has pleased our critics to inveigh against bureaucratic control of artists, this in fact does not exist and has never existed. No-one -except the critics-has ever told the artists what they should paint…’

Had anyone, in 1939, told someone who had met both men that they would have such a harmonious working relationship as they did, he would not have been believed, for two such disparate men would be hard to invent. It was probably due to their shared passion for their jobs.

The book is interesting after this lapse of time, not only for the quality of the work illustrated, but also to see more clearly the influences that shaped his later output: there are touches of Russell Dry dale’s landscapes in the oils glimpses of Topolski in his pencil sketches of , say, soldiers playing cards at night while waiting for the transport that always took so long in the Army; glimpses of the British Graham Sutherland in some landscapes, and of Henry Moore’s sculptures in some of the figure paintings.

But the line sketches of figures are pure Donald Friend-or are they just very good line drawing?

Leave a Reply