IT is fair to say that ten or fifteen years ago, any Australian academic historian who set out to write a full biography of an Australian military figure would have been regarded as an oddity. Acceptable work could be done in Labor’s historical role and political organization of trade unions allured many. A few might be observed dabbing in an interpretation of our past which appeared under the generic title of ‘the new left’. Naturally, not all the professions succumbed. Still, it took more than a little courage to announce to an academic gathering that one’s interest lay in defense and foreign affairs. It was much better to say nothing than admit a wish to write about things military. Now this attention to the Labor theme which dominated and discipline is healthier for it.

Not that the written history lacked scholarly merit-the problem was that taken together it distorted the past. In it, Australian society tended to polarize. On the other a conservative, elitist, obstructionist, Imperial minded group of capitalist employers whose aim was to thwart the social, political and economic aspirations of the working-class. In crude hands, and with more enthusiasm than evidence, such people might even have been termed fascist. Simply, it would not do. Indeed, it is possible that this scenario got as boring for its practitioners as it did for their readers. If nothing else, it meant that those at the Labor end of the political spectrum were either seen in negative terms, or were ignored entirely. Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash, Australia’s most famous soldier, was such a one. Dr Searle’s very fine biography of him is most welcome.

Monash was born in 1865, a child whose Jewish parents had recently arrived in Victoria from Germany. Gifted at school, he at first failed to realize his potential at Melbourne University. It took him more than ten years to complete his engineering degree and Arts-Law. Nevertheless, he worked as a civil engineer, a successful advocate, became a businessman, militia officer and social climber. In and out of ‘sexual’ relationships (Searle is not always explicit) he married, became a father, separated from, and then reunited with his wife. At the turn of the century there was no glimpse of his future fame yet by 1919 he was a much decorated soldier, lionized and a national institution. In 1920 he was appointed foundation chairman of the State Electricity Commission of Victoria. Eleven years later he died, and not long afterwards was virtually forgotten. Dr Searle may well have made certain that he will not be again.

Although national recognition came to Monish solely through the experience of war. Searle’s study is by no means a narrow military recital. Unlike that of his professional counterpart, a citizen soldier’s military career occupies a brief period in his life. Thus it was with Monish. Consequently, this biography is as much a social history as it is military. It makes a contribution to Australian business history and to understanding the development of civil engineering as a qualified profession. Conflicts between militia officers and permanent soldiers marred the army through to the Second World War. Searle, quite rightly, sets Manish’s pre-war military. It makes a contribution to Australian business history and to understanding the development of civil engineering as a qualified profession. Conflicts between militia officers and permanent soldiers marred the army through to the end of the Second World War. Searle, quite rightly, sets Manish’s pre-war military career within this framework. From 1920 we are also given a quite fascinating account of the politics involved in setting up a state instrumentality. Always, however, the focus is on the man involved in such activity. Always, activity. Searle never allows Monish to move off-center. Events are presented through his eyes, bewildering eyes though they seem at times.

Monish was certainly a ‘difficult young man’. Searle himself is moved to remark that as far as women were concerned he was a ‘public menace’. Great commanders have often shown a deep need for the feminine comforts. Nelson and Napoleon are but two such cases. With Monish, however, one feels that the drive had darker origins. Quite deliberately he set out to exploit, possibly sexually, but unmistakably psychologically. It was a cause for sadness. Searle’s account of an affair with the wife of an assistant is harrowing. Discovered, Monish received a humiliating beating from the husband. For some, maybe, a classic romantic occasion. For Monish, however, and his private diary is evidence, it was surrounded with a calculating self –deception. At the time of this episode, he was already courting his future wife and casting a speculative eye over other candidates. He needed pliable women, at his worst complete domination. It was this factor which contributed to his unsatisfying marriage. Searle is reticent, but Monish remained far from faithful. Within months of his wife’s death he installed his mistress of some years in a Melbourne hotel. Such behavior poses a question: was Monish a sensitive, aware man, or a card posturing as one? Unimportant? – Maybe. Another commentator, however, might find that an answer has a bearing on his later style of command.

By the time he had reached middle age, however, it did not seem a likely proposition that he would ever receive a serious military command. After fourteen years of soldiering, he had become a major. The depression of the nineties, however, had seen his business interests suffer, his employment lost and his financial commitments increase. Early illusions of outstanding success had disappeared. A description of him then: a black- mustached pale faced Jew, forlorn, anxious and dejected of mien . . .’ is not happy. It was the lowest point of his mature career. Searle’s skill might be measured by the fact that he can show us precisely how Monish moved through this period to become some thirteen years later a pillar of Melbourne society. By 1914 he had interstate business interests through Moniker Pipes and Reinforced Concrete, and in today’s values was worth over a million dollars. It remained true, however, that by 1914 Monish was serving in what would have been his last military appointment before retirement.

It was the 1906 conscription act, the reorganization of the ramshackle Australian military forces by British officers aided by some outstanding local professionals, plus the leadership of Alfred Dakin which gave Monish a peacetime opportunity. He left the Garrison Artillery, with which he had served since 1883, and acquired the rank of Lieut. Colonel the newly formed Intelligence Crops. In July, 1913, he received his first infantry command, and as a full colonel, was placed in charge of the 13th Infantry brigade. From Searle’s evidence,it should be safe to assume that it rapidly became the best organized, trained and administered brigade in the country. As the inspector-General of British Over- seas Forces, land Hamilton, was heard to remark, Monish had the making of a commander. Some eighteen months later, there was the chance to show if Hamilton had been right.

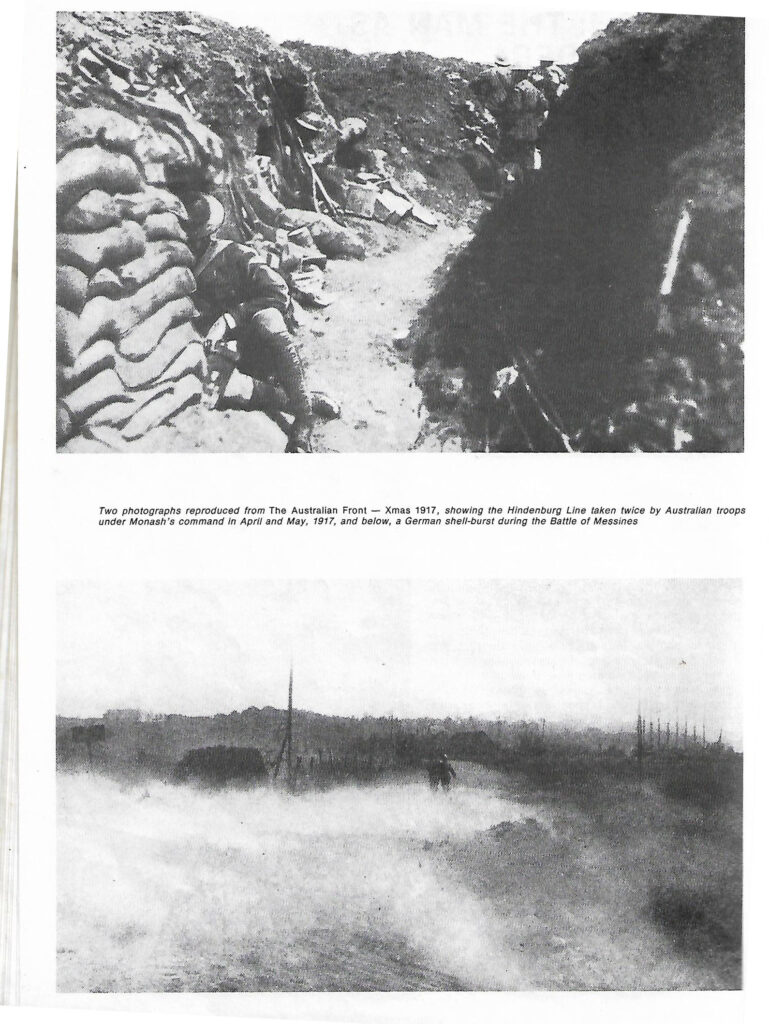

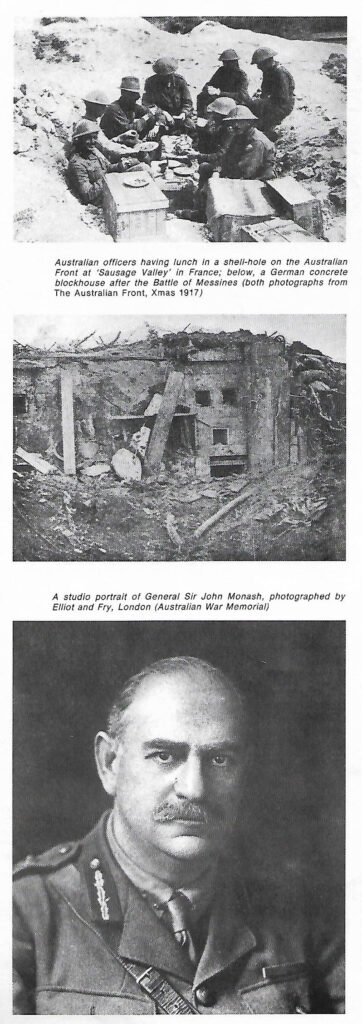

Apparently, he was. Monish, given the command of the 4th Brigade at Gallipoli, emerged from that general shambles with his reputation greatly enhanced. Searle revises to some extent the less than friendly account exhibited by C.E.W. Bean in the official history. Through Searle, we see Monish leading his Brigade with compassion, understanding, foresight and some moral courage. One example may suffice. Planning for an attack on 2 May 1915 had been designed to provide a link with the New Zealand Brigade. Although relatively junior, Monish had no hesitation in objecting to the plan in spite of opposition from senior officers. Overruled, he made his own preparations with dedicated thoroughness, carefully briefed his own officers and made sure that his soldiers understood the precise task. The attack, as predicted, failed, and with heavy casualties. No colonel, though, could have done more to prevent it. After the war, even Bean was to argue that one Monish-directed defensive action by the 4th the Brigade deserved to rank as among the finest feats of the AIF throughout the war. Monish left the peninsula marked for Divisional command.

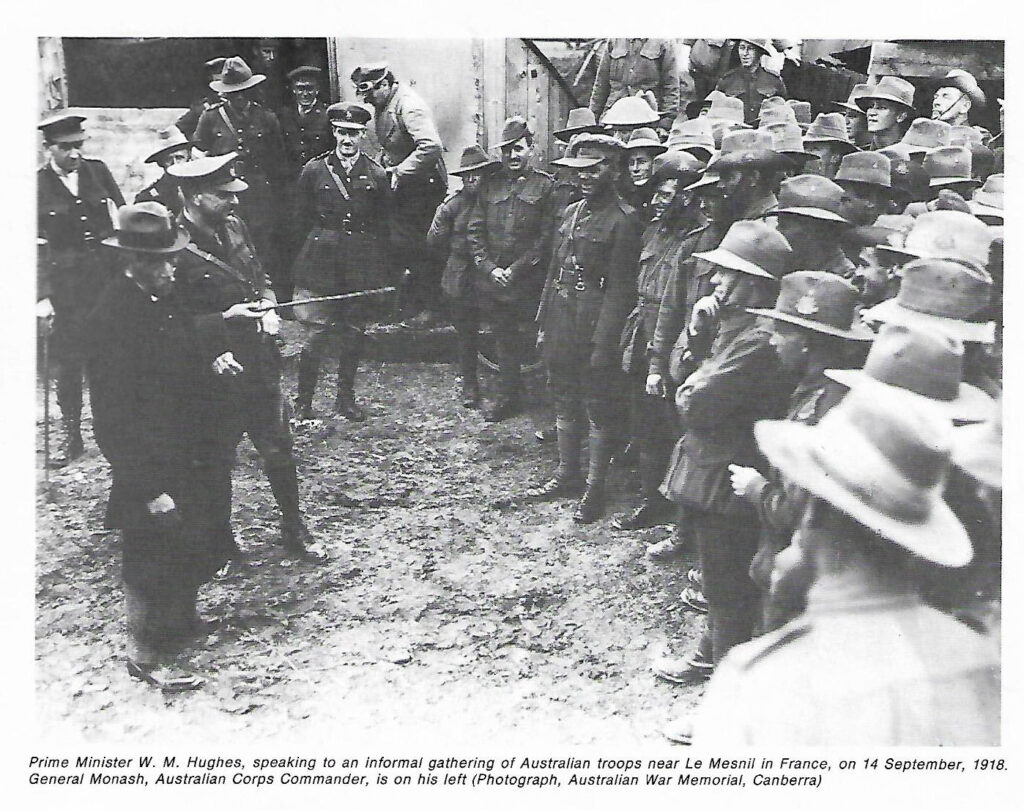

It can be argued that although Monish was to become the commander of a five-division corps, his organization, training, administration and deployment of the 3rd Australian division marks the real summit of his military achievement. His strength lay in planning and preparation, personality traits which had been nurtured from youth. St Paul is said to have observed: ‘There is one glory of the sun, and another glory of the moon.’ For those of such persuasion, the battle is radiance, but without the moon guiding the patience and tedium of preparation it faces eclipse. Monash, above all, realized that the battle of training always had to be won, and he carried out this task superbly. Teamwork and consultation underwrote his method and a division was still small enough to subject the whole to his personality. It has been said that he knew which particular duckboard in what trench needed repair. Thus when the division fought it was as a unit supremely confident in its leader. Its first victory at the Battle of Messines is evidence enough of this. Manish’s further military career is a simple demonstration of the axiom that war is the natural fertilizer of ambition crossed with ability. From being an obscure militia colonel in 1914, and a brigade commander in 1915, Monish when appointed corps commander in June 1918 found himself responsible for a hundred and sixty- six thousand men and had under his command five major- generals and twenty five brigadier- generals. And he was just in time for the victories of August 1918. Hamel, his first battle, was a brilliant success. For the first time, thanks were used correctly, and the operation furnished the model for almost every British infantry attack with thanks throughout the remainder of the war. When the Hindenburg Line was broken, following the august counter-offensive, the fighting on the western front was close to being over. Searle does show that Monish later overrated the role of the Australian troops in his Australian Victories in France, but their presence was crucial, and so was that of Monish.

The aftermath, the return to civilian life, might seem to be an anti-climax. Not so. The organization of the State Electricity Commission demanded the use of many talents. But perhaps nothing quite became him after the war as much as his utter refusal to have anything to do with the extreme right-wing groups which flourished in the Depression. By some he was certainly typecast for the role of a Mussolini. There was the masterpiece of a reply to one Sydney-based cabal. They were told that he had ‘no ambition to embark on High Treason’. Moreover, if his leadership were trusted, then so should his judgment and reliance on democratic forms. He died shortly afterwards, worn out by a lifetime’s work and from the unrelenting responsibility of the war years.

Monash was a complex man, at times hard to like and difficult to admire. The war, however, wrought changes in his personality: the man of 1914 was not that of the twenties. Then the characteristics which often make a great commander become much clearer. Capable of applying harsh discipline, it was never for trivial matters. In war, he lost his authoritarian traits. Delight was found not only with women but also in music and wide reading. What he lacked in humor was compensated for in kindness and consideration. As Searle sadly remarks, Manish would have made a good father of a dozen children. The machismo image of many a present day Australian male would have met with his distaste. Without doubt Monish deserved this biography and we should be grateful that it has been provided.

Leave a Reply