Japanese, except in its extreme forms, has nothing to do with either Chinoiserie or Japonaiserie, two forms of pretty superficial toying with Asian concepts. These later influences were either invented by Europeans imagining what Japanese or Chinese art should be or carried out by shrewd craftsmen in China or Japan to cater for a European market that carved the new.

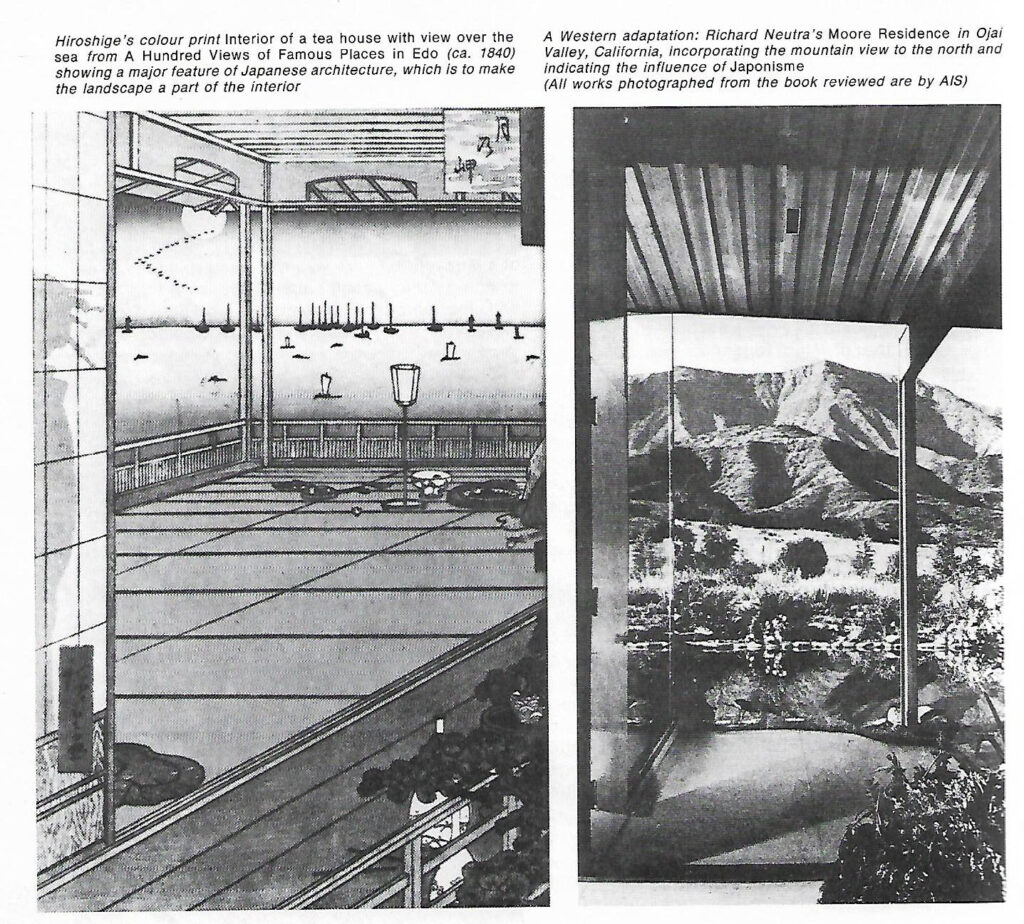

Japanese, especially as this splendidly produced book describes it, refers to the profound effect produced on European artists in many fields by the importing of Asian works. One strong impact concerned perspective: it is easy to imagine the stunning effect that a wood-block print such as Hiroshige’s extraordinary perspective – a close-up of a swooping eagle high above the old city of Edo- would have on artists in Europe Eager for the new.(See frontispiece).

It is difficult to date the beginning of the influence of Japanese art on Europe. Chinoiserie had been current for a century or more before it began. The author of this book, professor of Art History at the University of Karlsruhe in Germany, and formerly chief curator of the famous Pinakothek in Munich, dates Japanese to 1854, when Commodore Perry forced open the ports of Japan to the West. The English painter Rossetti learnt of Japanese prints through James McNeill Whistler in 1863.

A good deal of impetus was given to its spread by the big international exhibitions and the founding of the magazine Le Japon artistique in 1888 by Samuel Bing, a Paris art dealer, who also organized gallery exhibitions of Japanese art.

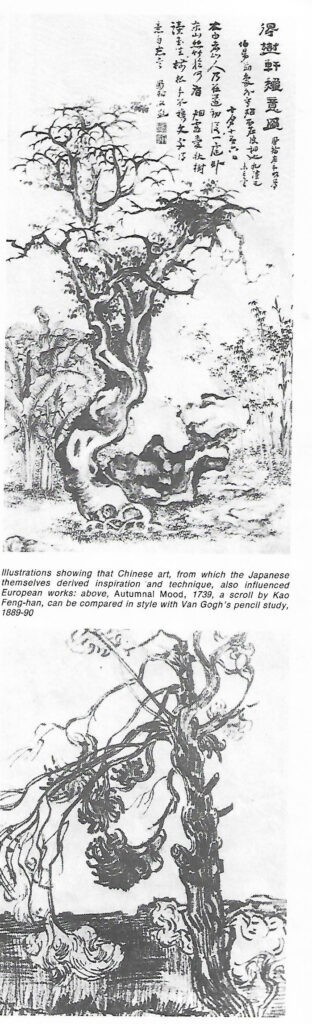

The cult of Japanese spread widely: many artists found new forms of perspective in the bold achievements of Japanese printers. Whistler in particular benefited from Japanese painting and so did Van Gough, Monet, Mamet, Gauging, Degas, Signac . . . potters early seized – and still seize, world-wide on the superlative models of the Japanese, inherited via Korea from China, but as in many cases of their borrowings, line and design were simplified.

On the fringe, people dressed up in the Kimono and had their portraits painted trying to look exotic. Some painters, including Cinder (Hemisphere June 1974) did fan- shaped paintings to imitate Japanese decorated fans.

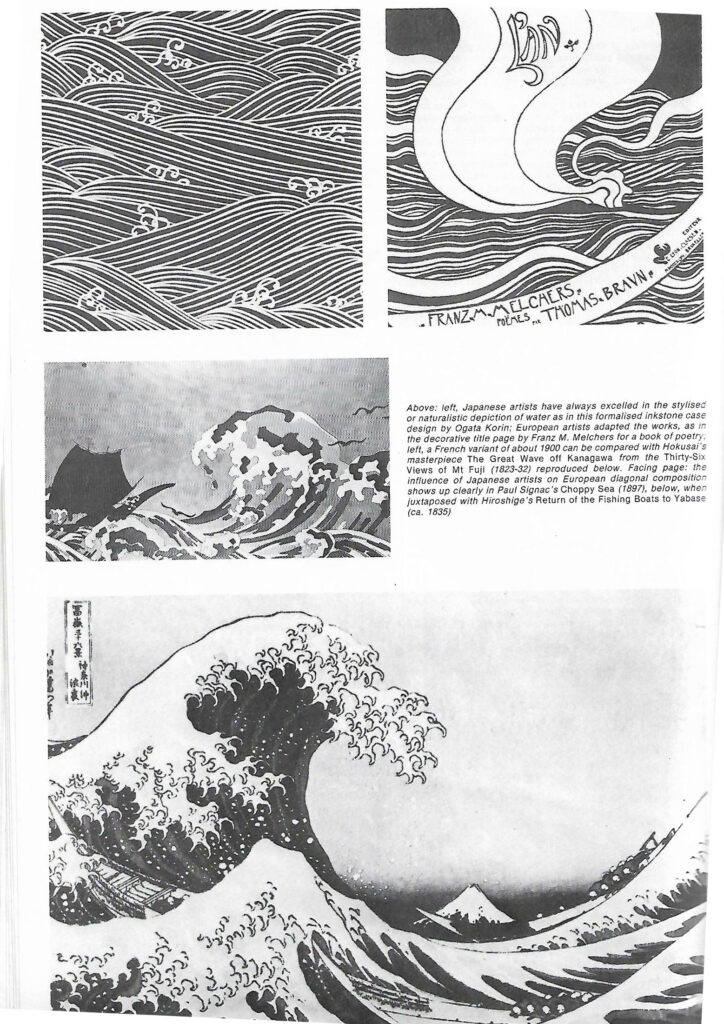

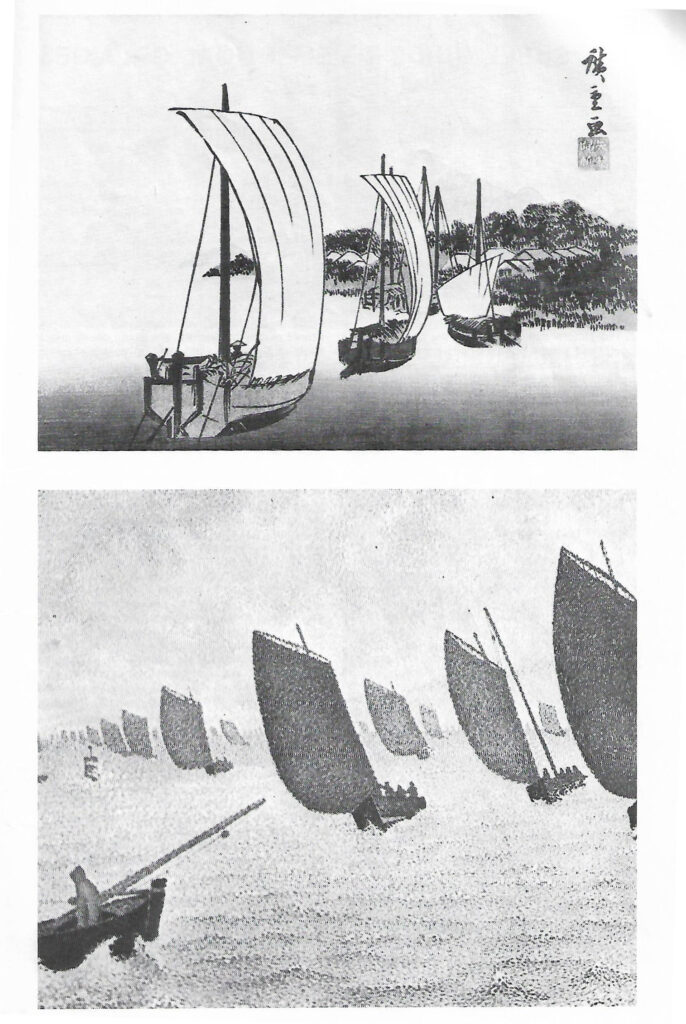

The moon, or stylized crest, has become the somewhat overused logo of today and I am afraid that the master of landscape, Katsushika Hokusai, must be held responsible for the flight of wild ducks in factory- made pottery displayed at forty-five degree angles on many Western living-room wails; the original concept probably dates back to his wood- cut of 1823, called birds, for it was from this and other works of art from Japan that the Europeans learnt diagonal composition.

A couple of spectacular juxtapositions in Japanese show other clear influences: Hiroshige’s Sudden Downpour in Shone from the Hokkaido series with bearers walking uphill in what has been described as one of the most striking depiction of a rainstorm ever done by an artist had a clear influence on the French painter Henri Riviera in his Funeral Under Umbrellas. Even more convincing in its demonstration of closeness of design is in Hiroshige’s Tango (from the Famous Places from More than Sixty Provinces) and Kirchner’s November.

It is not surprising that the Japanese love of water should have influenced the Europeans, from the inspirational treatment of van Gogh to the near plagiarism of Hokusai’s masterpiece The Great Wave in a French painting of 1905, the wave, showing a small, fail vessel about to be engulfed by a curved stylized mass of poised water. ‘Hokusai’s wood-cut,’ says the author, ‘had a formative influence on the wave painting of generations of painters.’ And indeed, it was so, for Beardsley and many others used swirling designs of water in Japanese paintings in their works, not necessarily related to the original subject, but designs were easily adapted to other needs.

In their treatment of trees, too, Japanese painters influenced their European colleagues: ‘ Hokusai could line up a row of pine trees so that they are in constant motion . . . Felix Valletta [a Swiss painter who worked in Paris] took this image further and grouped trees to form a single canopy.’

The number of artists who benefited and still are benefiting from the influence- architects, painters, potters- include many more than those mentioned in this brief review. Toulouse- Lautrec, one of the great innovators in French art who brigade the gap between salon painting and the popular- oriented posters he did, painted on fans, and the painting of screens was taken up by, among others, Chagall and Paul Klee, whose beautifully naturalistic five-fold screen Landscape on the Aare, not far from his birthplace in Switzerland, is very different from his later abstracts.

There were less successful attempts by Europeans at calligraphy or pseudo-calligraphy, which, compared to the originals they vainly tried to copy, frequently show a total lack of assimilation of something that is an accepted art from in China, Korea and Japan.

But overall, the mixture has worked well, and not only one way, for many Japanese painters, including Shaba Kokan (Hemisphere January and March 1977) and many other Japanese adopted European art-forms. And after all, there is no reason why one culture should not continue the age-old mix that has been going on for centuries-now more speedily than ever before.

Leave a Reply